In May of 1972, President Richard Nixon took the unprecedented stop in Moscow. Accompanied by his wife, Pat, his secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, and a host of other American officials, Nixon arrived on the heels of his also unprecedented February visit to Beijing. The combative relationship between the United States and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) had culminated in the ongoing Cold War, which came with the possibility of nuclear war. It had only been a decade since that possibility careened toward probability with the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.

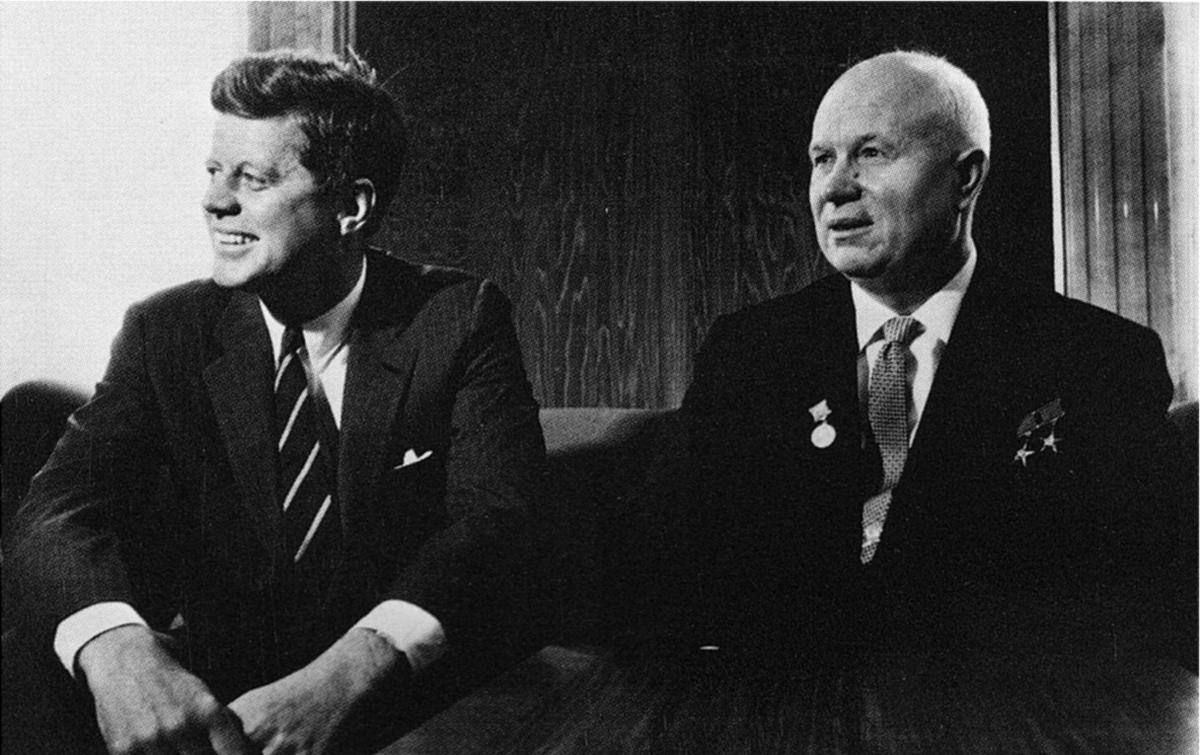

John F. Kennedy and Nikita Krushchev meet in Vienna prior to the Cuban Missile Crisis. Public Domain