The holidays have come and gone, as have the rich, stodgy foods of the season. When you’re surrounded by Christmas lights, decorations, and jolly music, all you crave are fatty meat stews, warming creamy soups, and decadent chocolate cakes.

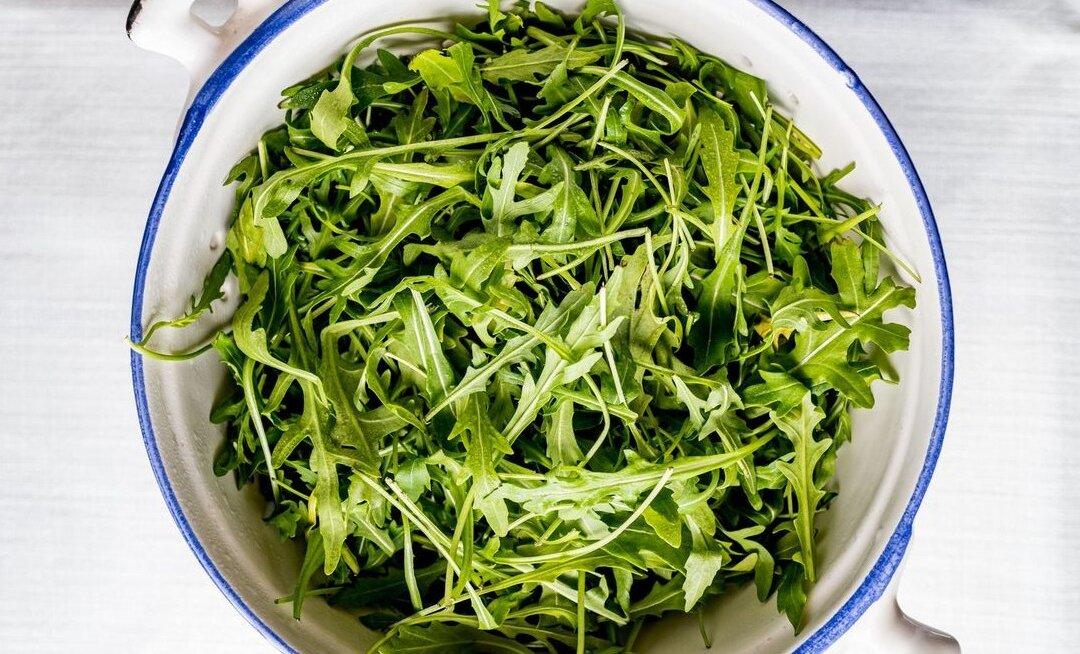

But now that the festivities are over, what are left are winter’s frigid temperatures, cold, clear skies, and biting winds. This is when I find myself craving foods that reflect the season: crisp, clear, and bitter.