In 1716, poet Alexander Pope received a letter from writer Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who had just seen a performance of “Angelica vincitrice di Alcina” in Vienna.

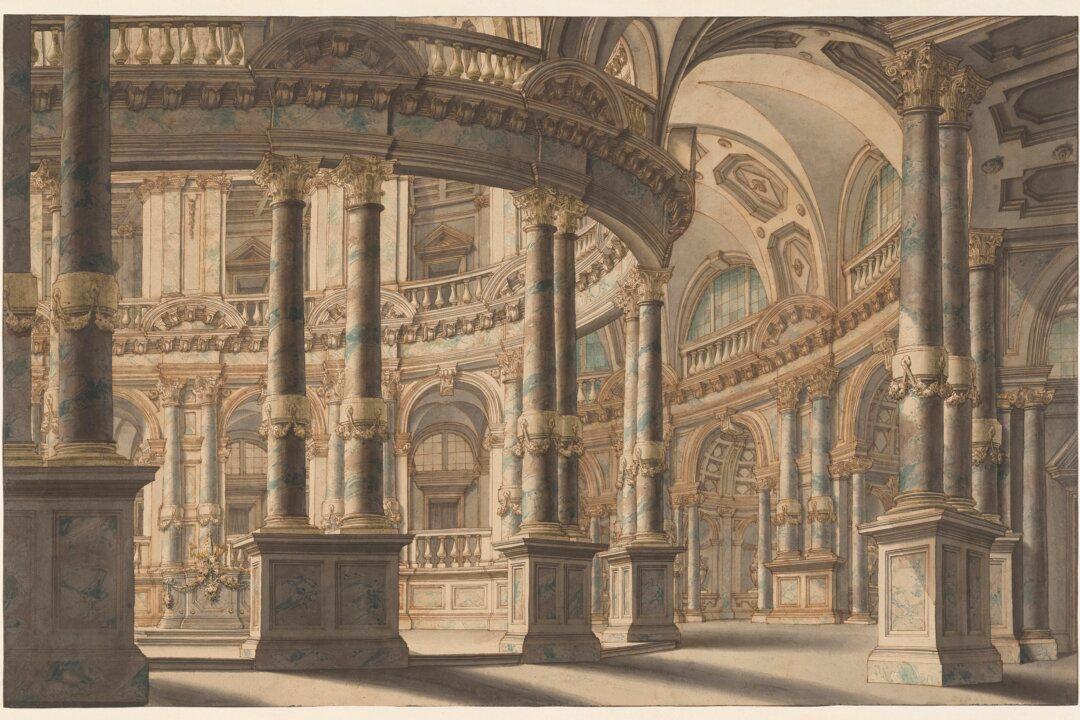

“Nothing of the kind was ever more magnificent; and I can easily believe what I am told, that the decorations [sets] and habits [costumes] cost the Emperor thirty thousand pounds sterling [over $4.1 million today],” she wrote, as quoted in the exhibition catalog for The Morgan Library & Museum’s “Architecture, Theater, and Fantasy: Bibiena Drawings From the Jules Fisher Collection.”