Today, most people are familiar with Latin chant because of the way it is inserted into film scores, especially in moments of fear. In the “Lord of the Rings” films, the chanting signals the arrival of the Nazgul, and the viewer can expect to see riders in black chasing Frodo through the woods.

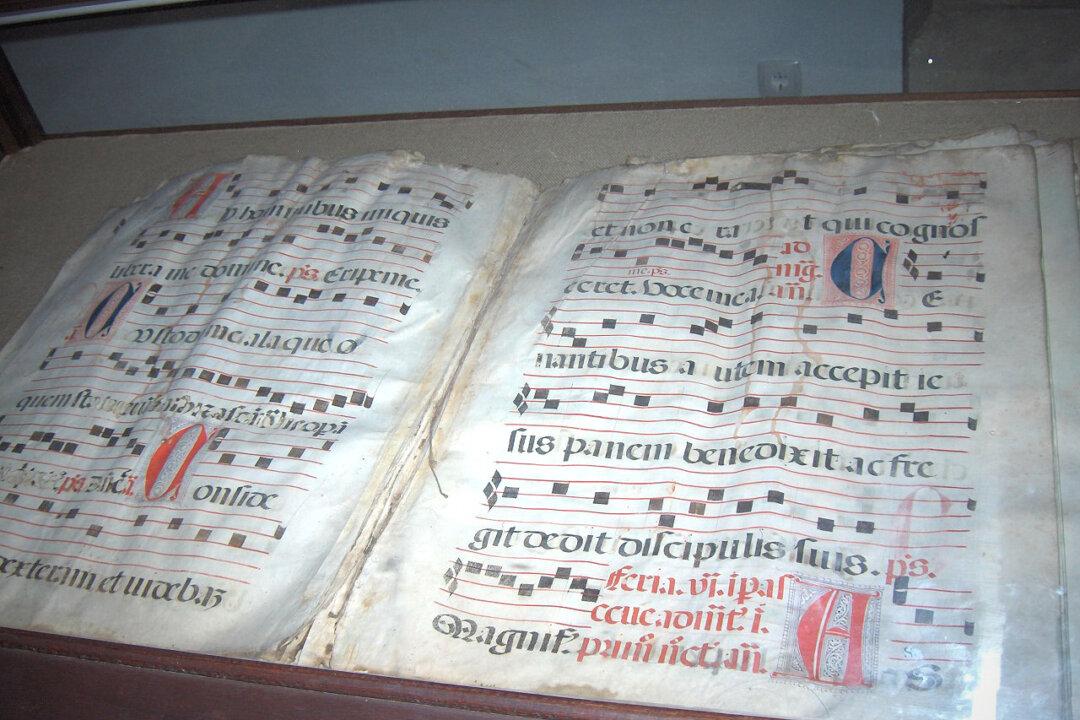

But Gregorian chant used to be associated with praise and joy rather than horror. It was also much more complex than its modern adaptations which, by repeating one or two phrases over and over, are designed to elicit a simple emotional response from an audience. Given that plainchant has no instrumental accompaniment and is monophonic—that is, all the voices sing only one line of melody—this may seem surprising.