NEW YORK—It may be that the brightest flames burn out the fastest. Whatever Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux was put on this earth to do, he had only 48 years to do it before his battle with cancer consumed him completely.

Carpeaux was born in 1827 during the reign of King Charles X, which lasted only six years until Charles was dethroned 1830. His successor did a bit better, ruling 18 years before being overthrown himself. By the time Carpeaux succumbed to bladder cancer in 1875, France would have experienced presidency, dictatorship, a couple of wars, and the Paris Commune.

Having lived during one of France’s most politically and socially unstable periods, it’s no surprise that Carpeaux developed the shipwreck as a metaphor for human life—inexplicable, painful, fleeting.

Yet his enormous artistic output only rarely displays the anguish that sickness and financial hardships wrought upon him, and when it does, it is honest, not self-pitying.

The Metropolitan Museum’s Carpeaux exhibition, the first since the centennial of his death, captures the bewildering contrast between the beauty in his work and the torment in his soul.

The exhibition consists of about 150 works, many on loan from Musée d’Orsay, Musée des Beaux-Arts in Valenciennes, the Louvre, Petit Palais, and other institutions in Europe and the United States.

Man Versus Marble

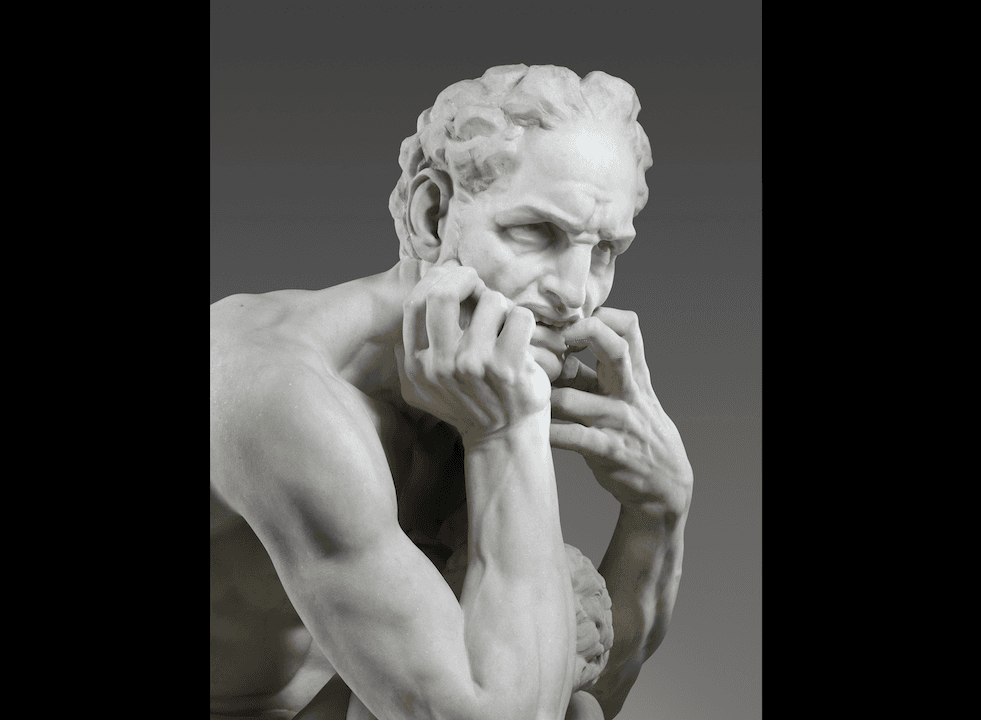

When Met Director Thomas Campbell asked exhibition curator James Draper to describe Carpeaux’s achievements, he replied, “flesh and blood in stone.”

Draper captured the artist best in his pithy remarks to the press on March 3.

“He was compulsive, outrageous, a more than difficult husband, a loving father. ... He will give you tears, smiles, but also make you feel like you know a person,” Draper said. “You feel not only flesh and blood, but that you know every corpuscle in a countenance.”

Carpeaux’s mythological characters are sweet and playful, and his portraits exhibit such sensitivity to character that you’d never guess their maker was a man with a fire in his belly—ambitious, enterprising, and not afraid to break some rules to explore new or costly ideas.

The only sculpture that demonstrates Carpeaux’s edgier side is the exhibition’s centerpiece, “Ugolino and His Sons,” a depiction from Dante’s “Divine Comedy” wherein the imprisoned Count of Pisa must decide between cannibalizing his children and grandchildren or die of starvation.

Carpeaux economized every gesture and pose to tell the story. Ugolino’s clenched feet, gnarled fingers, and pained expression speak volumes of his internal conflict. The way the eldest son’s fingers dig into Ugolino’s calf transforms stone into flesh and suddenly it occurs to us—what if this scene were historical fact?

Throughout the exhibition, studies in ink, terracotta (which Carpeaux sometimes handled blindfolded), and oil accompany each major work, allowing us to trace the iterations leading up to the final piece, as well as smaller reproductions made for mass market. This is as close as we can get to stepping into the artist’s atelier, where the patron’s vision and the artist’s vision, logistics, funding, master, and apprentice have to come together somehow to bring a work to fruition.

Humanizing Nobility, Ennobling Humanity

Carpeaux’s fortunes, though they were not great, rose and fell with the Second Empire.

His relationship with the royal family began when he followed Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie around as they traveled through northern France until they agreed to commission a marble.

Princess Mathilde, the emperor’s cousin and tastemaker at large, became Carpeaux’s champion and he became the art tutor to the young Prince Imperial (many versions of whose full-length portrait is featured in this exhibit).

Mathilde herself commissioned Carpeaux to do her one formal portrait in 1862. The 42-year-old looked self-assured and appropriately regal in lace and ermine.

A year later, Mathilde would ask for a more casual bust, a patinated plaster version, which is on display. Without the trappings of royalty, Mathilde looks like any ordinary middle-aged woman; blunt features, a little jowly.

The comparison between the two Mathilde portraits makes Carpeaux’s greatest talent crystal clear: He simply understands people inside and out, and his sitters trusted him because of that.

Madame Pelouze, a daughter of a prominent Scottish engineer, insisted that Carpeaux include her rather prominent curly chin hairs, and astonishingly to the modern eye (which is too accustomed to airbrushed photos of women), she looks no less beautiful for it.

Carpeaux was just as good with imagined personalities, as can be seen in his fresh and somewhat mischievous portrayal of Flora, Roman goddess of the spring.

He was always observing and sketching, letting delicacy play no role when an opportunity arose. “Mater Dolorosa,” which captures Mary’s grief at witnessing Jesus’s crucifixion, was based on one of his model’s own grief. Carpeaux had come across her crying in the street after the death of her son. Carpeaux lost no time in getting her into the studio where he let her sob while he sketched.

The Last Passions

The latter galleries take a personal turn with the engagement bust of his wife Amélie, a lovely portrait of the woman Carpeaux would spend their marriage maligning; she gave him four children, he spent all their savings to finance his projects.

The exhibit ends with four self-portraits painted between 1859 and 1874, as his health turned from bad to worse. The final one shows a haggard and hollow-eyed stare of a man whose mind was all too aware of the body’s decay. Even in his last works he displayed coherence and superb technique.

It’s a haunting note to end on, the question of what to do with shipwrecks. Carpeaux answered it with his burning desire to create something beautiful, lasting, and uplifting.

The Passions of Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

March 10–May 26

1000 Fifth Ave.

212-535-7710

metmuseum.org

Suggested admission $12–$25

The exhibition will continue to Musée d’Orsay in Paris, June 23–Sept. 30.