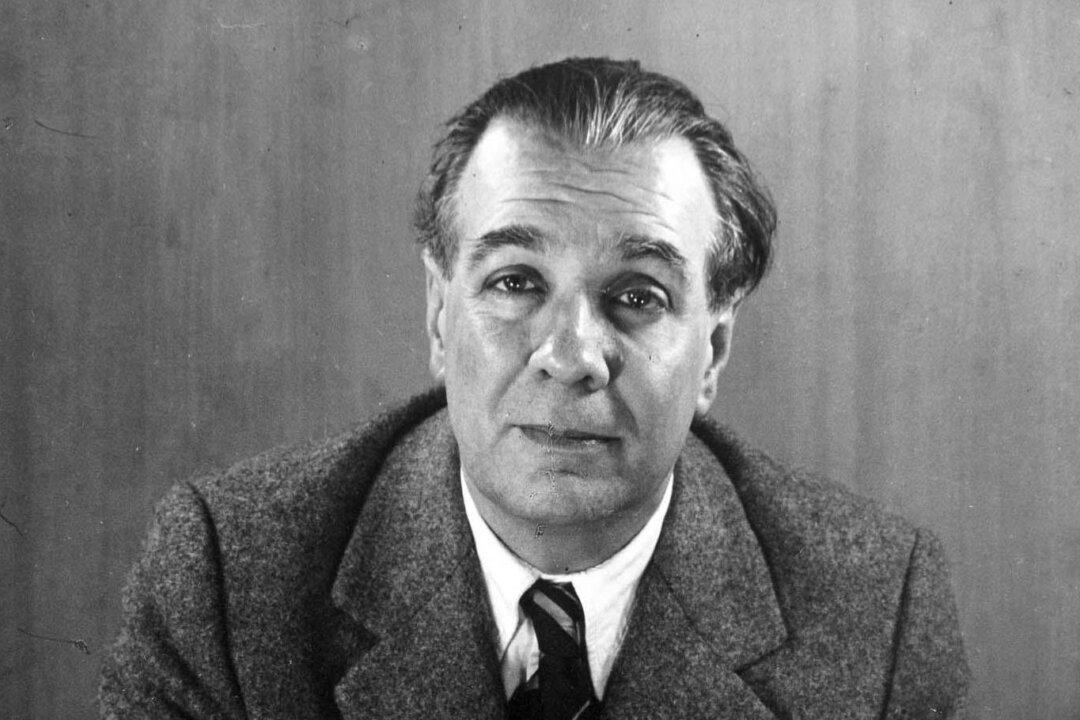

It’s no secret that Jorge Luis Borges of Argentina is one of the most outstanding authors in literature. His unique stories, which explore eternity, pain, time, and metafiction, have made him an obligatory reference in this field.

Despite his introverted character, the blindness from which he suffered in his last decades, and his undeniable inoffensiveness, Borges spent the last years of his life being canceled for his staunch defense of individualism by an academic and literary world increasingly committed to collectivist causes.