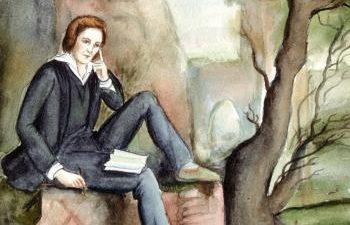

The poet’s eye, in a fine frenzy rolling, Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven; And as imagination bodies forth The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing A local habitation and a name. Such tricks hath strong imagination That, if it would but apprehend some joy, It comprehends some bringer of that joy; Or in the night, imagining some fear, How easy is a bush supposed a bear!

In this extract from Shakespeare’s famous comedy, the Athenian nobleman Theseus describes the peculiar nature of poetic vision. His tone is somewhere between caustic common sense and baffled wonderment.