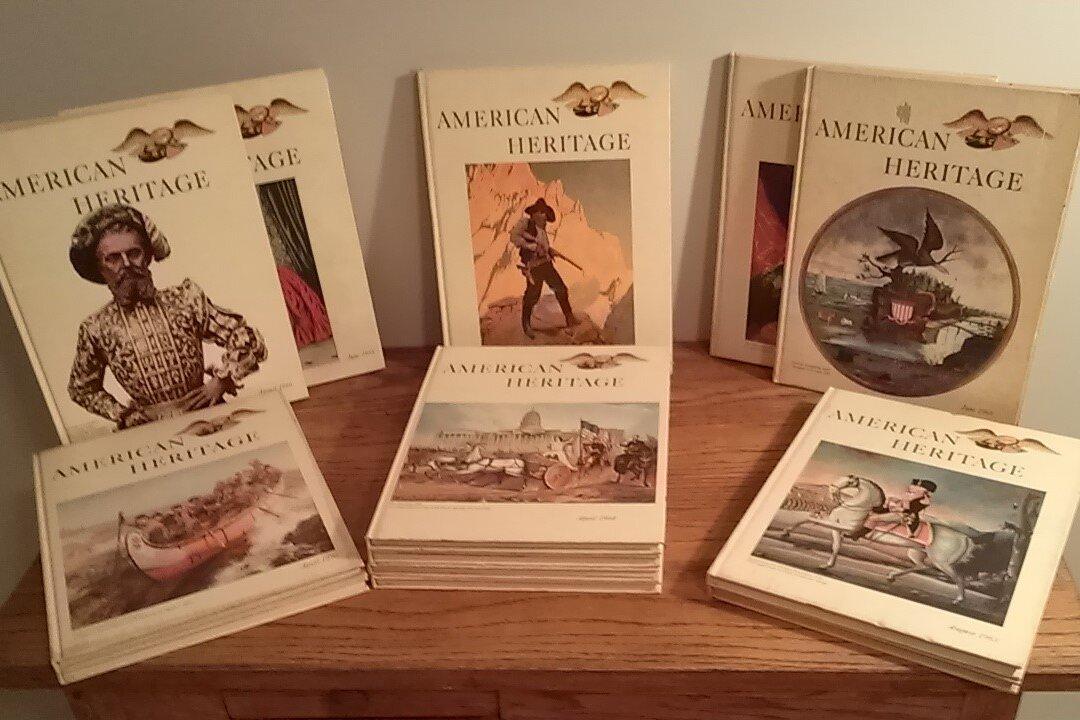

After my father’s death in 2016, his wife invited me to take whatever of his books I wanted. His college literature textbook—I’d read several of its essays and stories over the years—was my first choice. Second on my list was his collection of 19 American Heritage volumes. Ordered by subscription, these tall, slim books with their distinctive white covers were the remnants of a larger collection, publications that had arrived every two months in our house during the 1960s and early 1970s.

Recently, I opened a few of these volumes for the first time since bringing them home and was stunned. My reaction, I suspect, was much the same as someone today who watches the 1937 Disney film “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” and realizes that the talented cartoonists, artists, and other makers of that movie operated without computers. Similarly, in each of the American Heritage issues, which the company regarded as magazines, are marvelous histories and biographies replete with photographs and beautiful paintings and drawings.