“The magic garden has taken the place of the desert. He who saw the land three years ago and sees it again today, would think that some modern Aladdin had come this way and rubbed his lamp, or that Merlin had waved his magic wand and caused the Dream City to spring up.” —National Magazine, 1915Beginning with London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, international expositions showcased the power and cultural sophistication of the world’s leading cities. Immensely ambitious civic and landscape designs almost inexplicably transformed cities like Chicago around the end of the 19th century. Cities temporarily played host to these grandiose amusement parks and museum complexes with the might and prowess of classical antiquity. Strangely, these vast undertakings were by and large impermanent creations—strenuous efforts to be marveled at, then destroyed. In the early 1910s, California incredibly built two expositions that were underway at the same time only hundreds of miles apart.

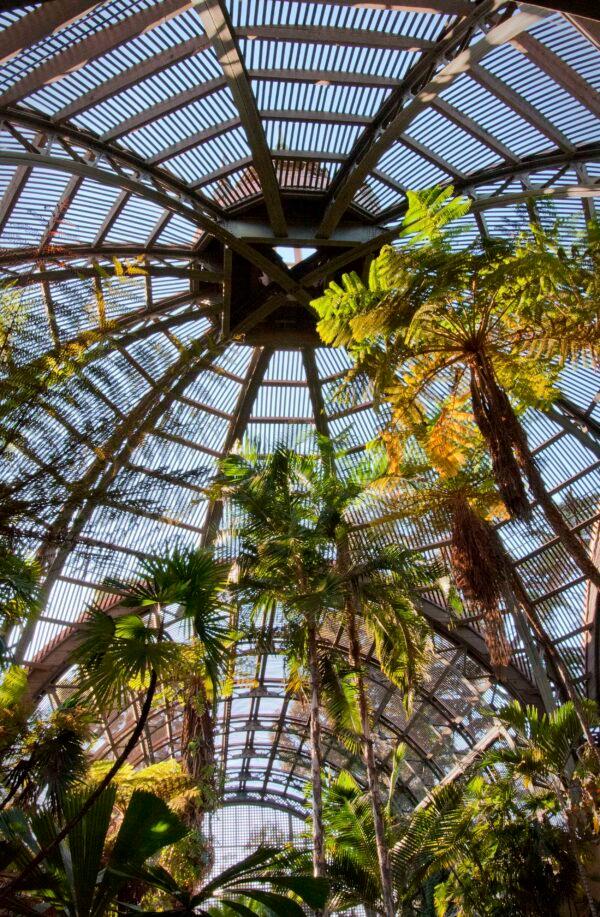

Palms expand into the 60-foot dome of Balboa Park’s famous Botanical Building. They flourish in the partial shade environment. Jeff Perkin for American Essence