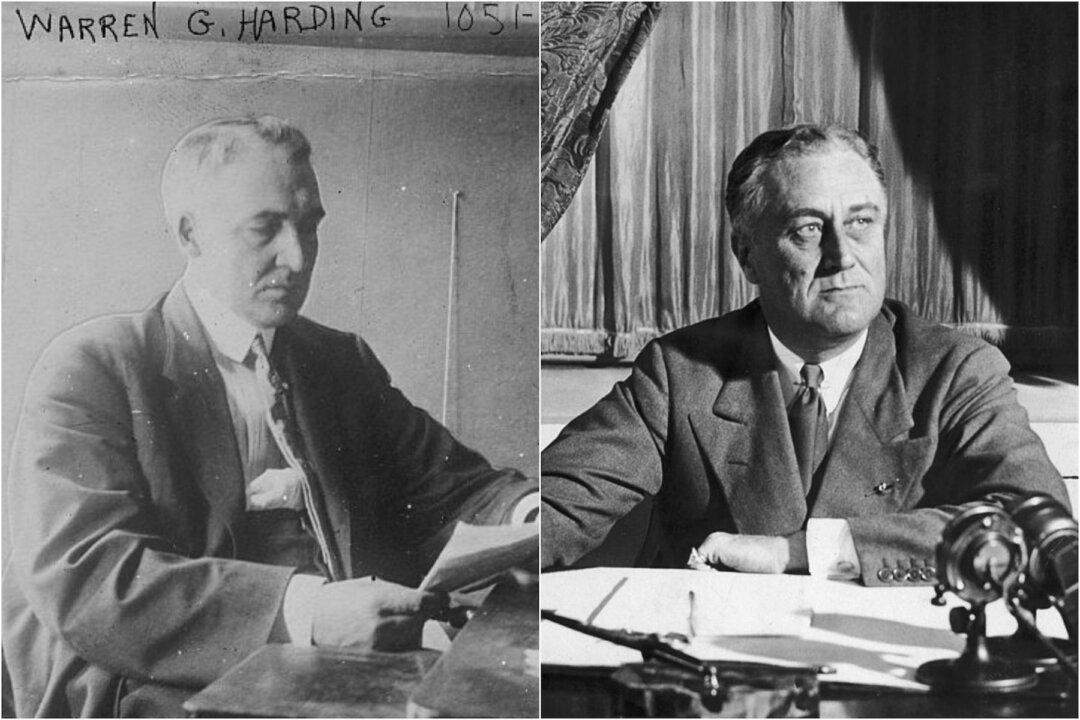

One is viewed as among America’s greatest presidents; the other perhaps the worst of all. One is hailed as a savior; the other as a failure. One is given memorials to enshrine his name for all time; the other is pushed into the sea of forgetfulness.

Driven by academia, this is where American history has placed Franklin Delano Roosevelt (in office 1933–1945) and Warren Gamaliel Harding (in office 1921–1923). It’s impossible to see FDR absent a “great presidents” ranking; it’s likewise impossible to see Harding absent the lowest rungs.