“Most arts have produced miracles, while the art of government has produced nothing but monsters.”

The 2 Monsters of the French Revolution Who Were Consumed by Power—and Lost Their Heads on the Same Day

Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, Maximilien Robespierre weren't seen as monstrous people prior to the Revolution. What changed?

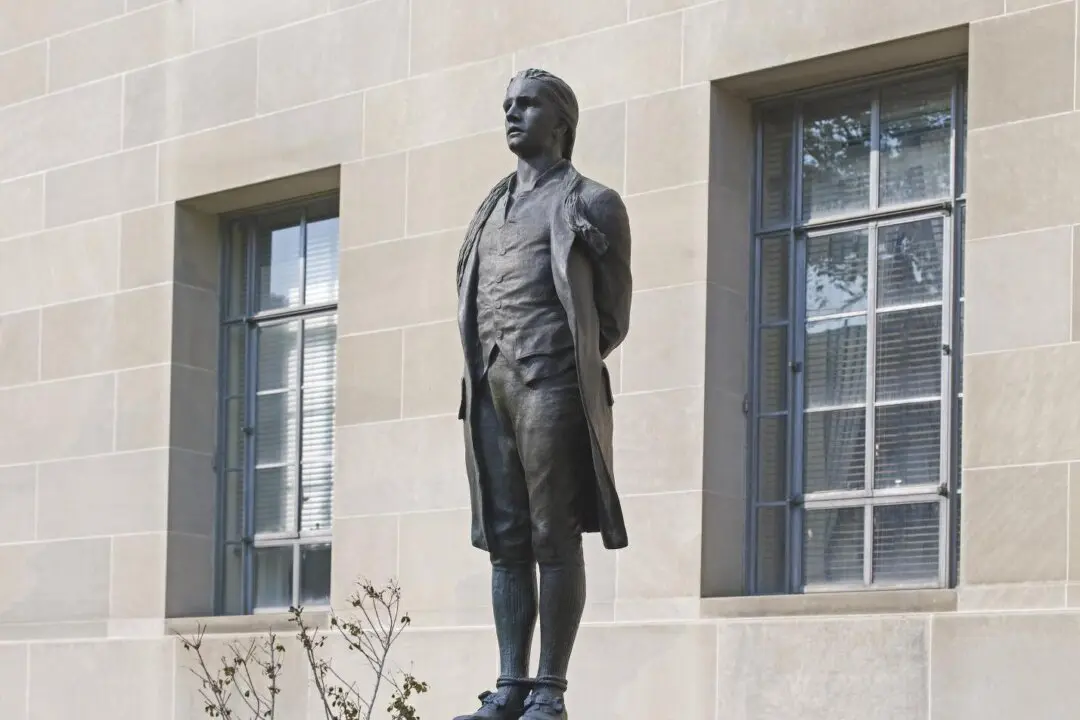

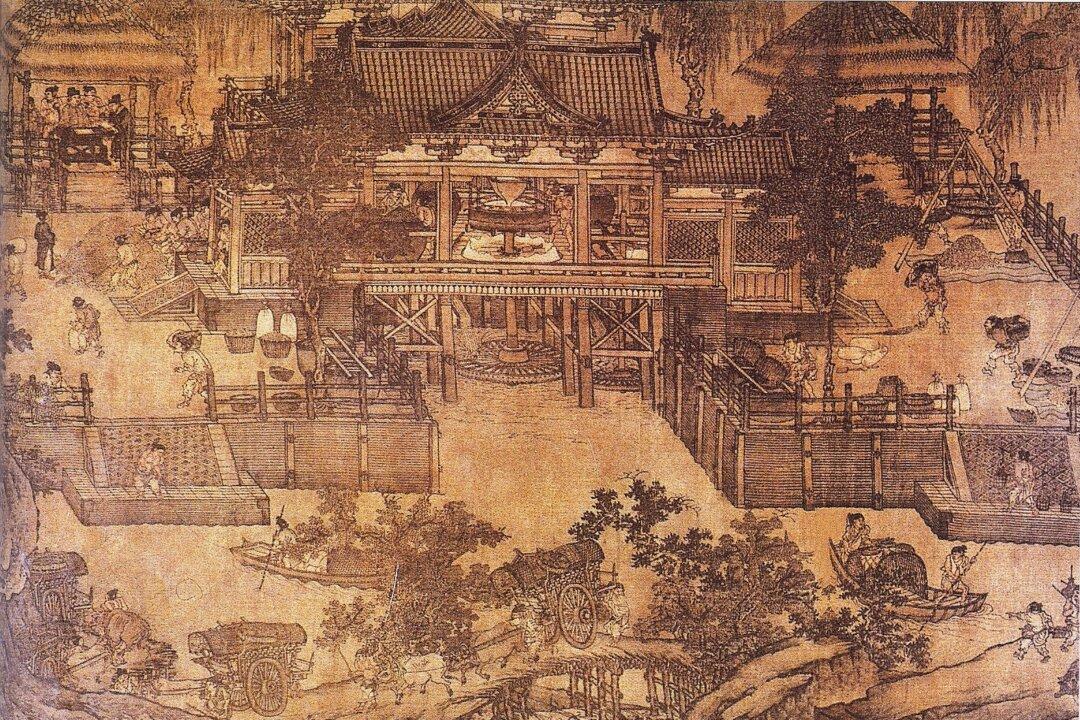

"French Revolution. Saint-Just and Robespierre at the Hôtel de Ville of Paris on the night of 9 to 10 Thermidor Year II (July 27 to 28, 1794)," 1897, by Jean-Joseph Weerts. Public domain

|Updated: