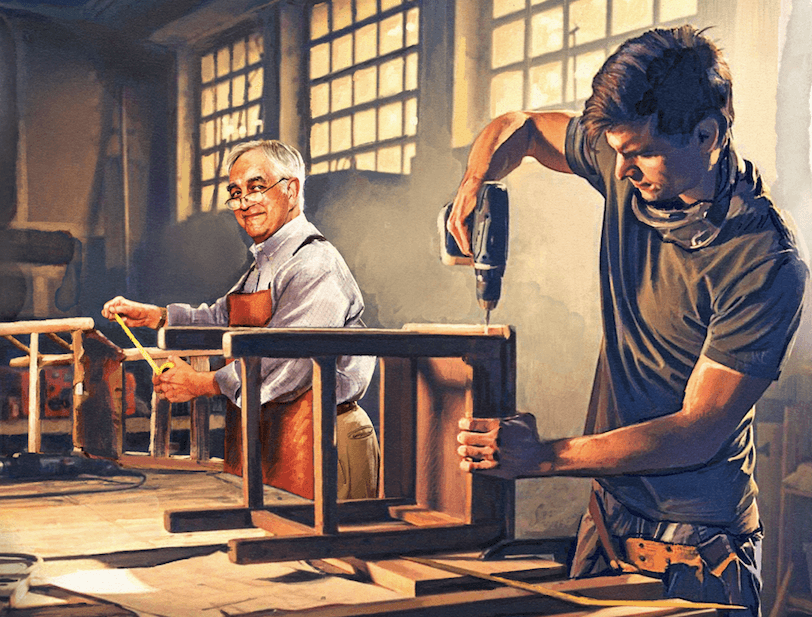

I happened to be on the outskirts of a conversation between a 17-year-old young man and a middle-aged married couple a few weeks ago. About to graduate from high school, the 17-year-old politely inquired as to what the husband of the couple did for work.

Soon, the two were setting up a time for the high schooler to come out and see the inner workings of the man’s business. Given earlier conversations with this man about how eager he was for good help, I imagined I could see wheels turning in his head at the prospect of the diligent, untapped talent that stood before him.