The internet is an astounding tool that links us to one another. It offers us an immense array of connections, ideas, and opportunities. But it’s also a web we can get stuck in.

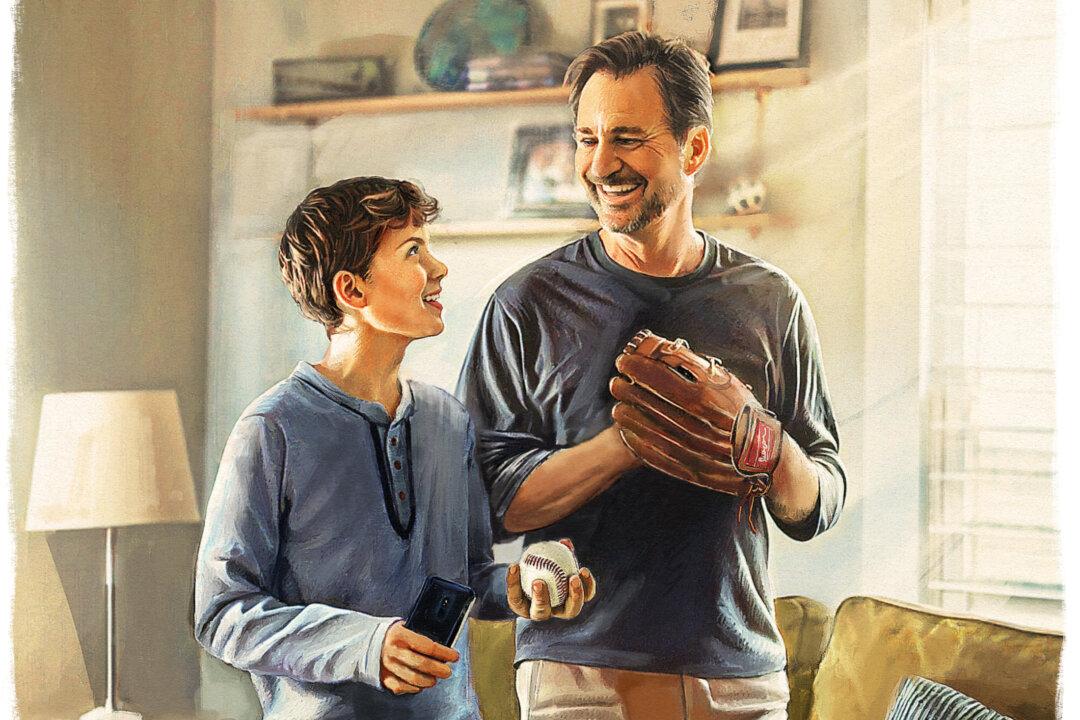

From social media addiction to YouTube rabbit holes to the Tetris effect to cellphones that seem permanently lodged in our palms, technology is a sticky thing to detach yourself from, and it has a way of slowly taking over your life, like a spider’s web in an abandoned house.