After 29 years in the FBI, I investigate privately, including cases of recovering stolen art. That puts me on email lists for major auction houses. Occasionally, I bid and am fortunate to add a piece to my own collection.

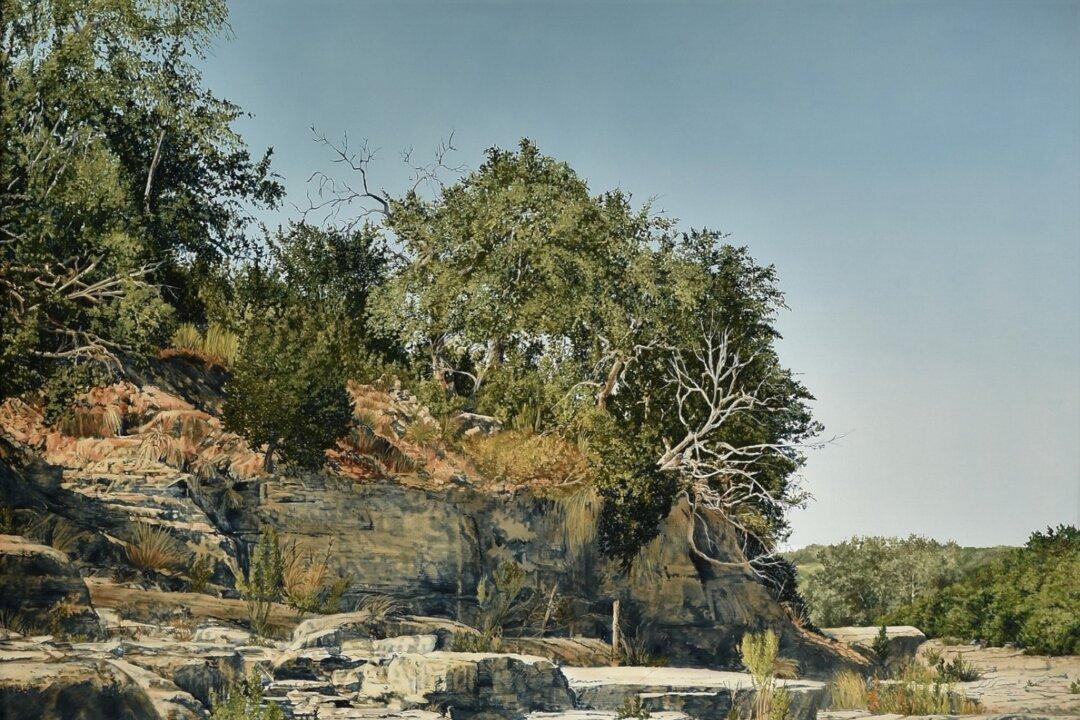

One painting from last year was “Stepped Rocks With Water,” a 1984 oil painting by Nancy Conrad, a Texas artist. She was commissioned by the Texas Commerce Bank to create 10 paintings, one for each branch, with the largest being the one I bid on successfully. I imagined I wouldn’t have much competition as the piece is 5 1/2 feet square, large for a painting today.