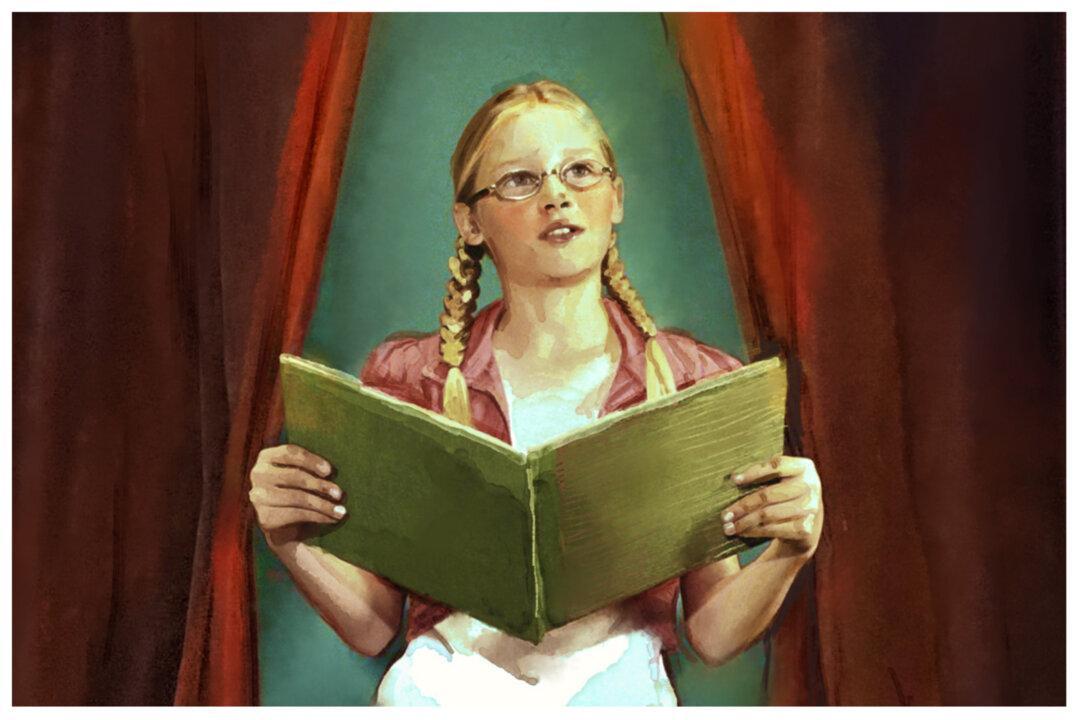

In the spring of 2014, I served as prompter for a local homeschool poetry fest in Asheville, North Carolina. From pre-K students to high school seniors, students marched onto stage and recited verse to an audience composed of family and friends. The little ones trebled out nursery rhymes, middle-schoolers delivered impressive reams of rhymes—Shel Silverstein’s “Sick” was always popular—and the high schoolers often aimed at the stars. My job was to sit in the front row with copies of all the poems, ready to help if someone stumbled or forgot a line.

The most impressive performance I witnessed in my three years as prompter was a rendition of T. S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.” The performer, Carolyn, had taken some of the seminars I’d offered to homeschoolers for several years, and I was aware of her academic and acting abilities, but that night, she dazzled me. She recited without mistake or hesitation, including the six opening lines in Italian. “Prufrock” is a free verse piece, long, with some rhyming lines but no particular meter. If you know the poem, you are now probably as impressed as I was. If not, you can read it here.