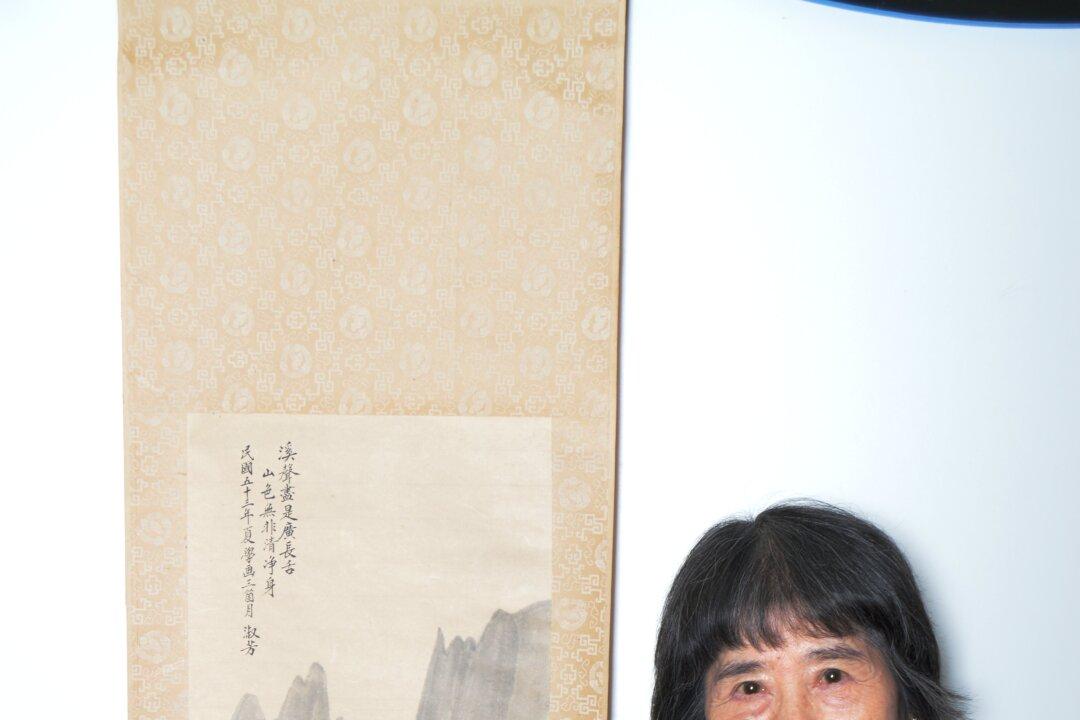

SAN FRANCISCO—“The most important thing is lifelong learning,” said Dora Shu-fang Dien, professor emerita of California State University, East Bay, when talking about her memoir, “Growing Up in Three Cultures.”

Her book, subtitled, “A Personal Journey of a Taiwanese-American Woman,” is first of all dedicated to her teachers. In the United States, she said, “when you graduate you are very happy, but in my days in Taiwan when we were graduating at any level, it was very sad for us. We were all crying because we were leaving our teachers,” she said.

She considers that emotional bond of teachers to their students—a combination of affection, high standards, and high expectations—as essential for good education. Teachers at that time didn’t just hold students to high standards; they themselves were held to high standards. For example, gambling and social dances were strictly forbidden for teachers.

In the United States, “we talk a lot about skills, a lot of emphasis is on achievement, and now we are also talking about social skills. In my days, in the traditional Chinese education, the emphasis was not in terms of social skills, but in terms of how to be a good person,” Shu-fang Dien said. Her great-grandfather, after passing the highest imperial examinations in Beijing, gave up his career as a government official to become a teacher, because at that time corruption was rampant, and it was extremely difficult for him not to become entangled in it, she wrote in her book.

In the American cultural context, she says she considers Melinda and Bill Gates to be good people. “They are kind and generous, dedicating themselves to the improvement of the lives of many people in the world, disregarding national boundaries. This is the spirit to cultivate in the education of our children.”

During her 3rd grade in 1945, the Japanese rule over Taiwan ended. Shu-fang Dien graduated as number one student from her middle school and was able to attend regular high school, although her father, a teacher and later a principal, had planned for the six girls of his ten children to attend the teacher-training high school.

When she was in high school, some among the refugees from mainland China who had fled the communists and come to Taiwan were highly educated. Those that became her teachers could not find a higher position because there were too few higher education institutions in Taiwan at that time.

“My high school teachers actually should have been professors at universities. These people were very dedicated to their teaching, they treated us pretty much like college students, and they had very high standards and all kinds of materials they brought to class with which to enrich the program—not just the basic school books,” she said. “I wrote this book to have the opportunity to thank my teachers.”

Romantic Love

Shu-fang Dien says her book “Growing Up in Three Cultures” is a case study in human development. After tracing in detail her ancestral lines and recalling her childhood, she gives excerpts of a diary she began writing, inspired by Anne Frank, while training to become a high school teacher.

The notes of her emerging romantic love towards an American studying Chinese culture in Taipei—and the complexity of the family situation this created for her when she wanted to marry him—are touching and captivating to read.

Without the consent of her family, she married the American gentleman and scholar Albert E. Dien. “He was very much like a traditional Chinese gentleman scholar, who loved books. That was what attracted me,” she said.

After sorting things out with her family and completing another year of studies in Taiwan, she followed her husband to the United States. The young couple lived in Berkeley, where he was pursuing his Ph.D. at the University of California, while she continued working towards her B.A. in education.

In her diary, she wrote, “If San Francisco is a gorgeous lady of a city, Oakland appears to be a shy country girl, coming out with her face partially covered by a thin veil.” Her pure-hearted observations and uplifting experiences from around 1960 are a great pleasure to read. The Golden Gate Bridge she describes as “graceful and ravishing” and “clad in red, forever captivating.”

She published “Growing Up in Three Cultures” in 2012 for family and close friends, publishing it in a simple paperback version, so that she could afford to buy many copies and distribute them to her numerous family members. All her other books were published as expensive versions by Nova Science, mainly meant for libraries.

“The publishers kept urging me to go to book fairs and book signing. I never responded to any of this because this book was not for public consumption. It is just for readers who might become interested,” she said. “My purpose is education, not money, not publicity, not my name, or whatever,” she said.

When asked how family and friends responded, she said, “They were all very enthusiastic; they loved it.” Her husband’s career later led him to become a professor at Stanford University. The secretary at her husband’s department said of the book, “Oh, once I started reading, I couldn’t put it down.”

Pursuing Higher Studies

When Shu-fang Dien married, her husband did not know whether he was going to get any job at all in the China field. “At that point he was just pursuing his interests,” she said.

Fortunately, after one year in Berkeley, he got a job at the University of Hawaii. Shu-fang Dien liked Hawaii, because it more closely resembled the culture, climate, and people she grew up with. She completed further studies there, earning a master’s degree with honor in Social Psychology.

After two years in Hawaii, the China field was opening up; the American government was beginning to allocate funds to offer scholarships in the field of Chinese studies, and Stanford University planned to establish a Chinese language program in a place where Chinese was the native language.

Stanford picked Taiwan, offered her husband the position of assistant professor at Stanford and head of this new program in Taipei, and the couple returned to Taipei in 1962, well received by enthusiastic journalists.

This allowed Shu-fang Dien to see her parents and “to show them that not only was the marriage sound, but also that I was able to pursue my own higher education. That was very important to my parents,” she said.

After two years in Taipei, her husband taught in the Asian Languages Department of Stanford University, while she took courses in child development. Two years later, her husband got an offer as Associate Professor from Columbia University, New York, and Shu-fang Dien and their son, Joey, moved with him to New York.

“My husband was very different. He would not consider the climate or the people. What was important was the next step, the prestige of the university. What I always did was to see what he was getting, and I tried to see how I could fit in, and still pursuing my own goals,” she said.

Thus in New York, she completed her Ph.D. in the Social Psychology Department at Columbia. When her husband obtained a promotion and a sabbatical at Stanford University, the family left for Japan for one year. After their return to the Bay Area, Shu-fang Dien got a position as a lecturer in the Child Development Department at California State University, Hayward (now East Bay).

The strong drive for lifelong learning, instilled by her teachers, inspired her to pass it on. She wrote, “I tried to instill the same enthusiasm for learning in my students during my teaching career.”

At California State University, an interdisciplinary program was initiated, called Human Development. It included lecturers from many fields, such as anthropology, biology, psychology, sociology, medicine, history, and literature, and would consist of lecture-hall presentations, panel discussions, as well as small-group discussions, limited to 15 students.

The students, most of whom would go into education and related fields, were encouraged to bring in their own life experiences. “We tried to give them a good general education, not so much focusing on the content but on the process,” she said.

“As psychologists, we know you do not retain much of the content of any lecture at all, but what you take away with you from your education is the method of learning and the attitude of learning,” she said, explaining why they had chosen this format of teaching instead of the more common method of lecturing.

When a student said, “You are my role model,” she felt very gratified, having achieved this aspect of traditional Chinese teaching.

Lifelong Learning

In her diary, Shu-fang Dien wrote, “I am always in search of something.” When asked whether that would still hold true today, she said: “I think what I mean when I say ‘I am always in search of something,’ is to be excited about new discoveries. It’s a general curiosity.”

As an example, she mentions the recent exploration of Pluto. “It is just mind-boggling that human beings can invent or create something like that to go all the way out so far. I guess I marvel at the human capacity to search and to find new things, to make new discoveries.”

“I guess I also have this kind of Taoist point of view from way back that human beings are part of nature.” She would watch nature programs with her son, who is now a neuroscientist at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland. “I feel very free and privileged to have retired. There is so much to learn outside of what I used to research.”

Looking at my recording device, she said, “it’s amazing, you see—such a small thing can catch so much information.”

In concluding her memoir, she wrote, “The ongoing process of growing up in three cultures feels more like a stew with the ingredients well mixed in a coherent manner, than a salad consisting of distinctive particles which can be separated out to savor the individual flavors. In other words, I do not see myself as a composite of a Chinese, a Japanese, and an American in separate compartments, but a Taiwanese-American with a strong sense of all these cultural influences in my background.”