When someone comes into our lives, we encounter that person in the middle of his or her story, in media res. We never fully read the pages of that person’s past, nor do we ever fully know what secret sorrows he or she carries. “Sympathy” by Emma Lazarus (1849–1887) mirrors life in this respect.

Therefore I dare reveal my private woe, The secret blots of my imperfect heart, Nor strive to shrink or swell mine own desert, Nor beautify nor hide. For this I know, That even as I am, thou also art. Thou past heroic forms unmoved shalt go, To pause and bide with me, to whisper low: “Not I alone am weak, not I apart Must suffer, struggle, conquer day by day. Here is my very cross by strangers borne, Here is my bosom-sin wherefrom I pray Hourly deliverance—this my rose, my thorn. This woman my soul’s need can understand, Stretching o'er silent gulfs her sister hand.”

The beginning places the reader in an encounter with two suffering souls without providing a backstory or explanation for the nature of this suffering. However, even without a complete understanding of each individual’s circumstances, our shared human weakness and our own experience with suffering enable us to sympathize with others and enter into their pain so that we carry it alongside them.

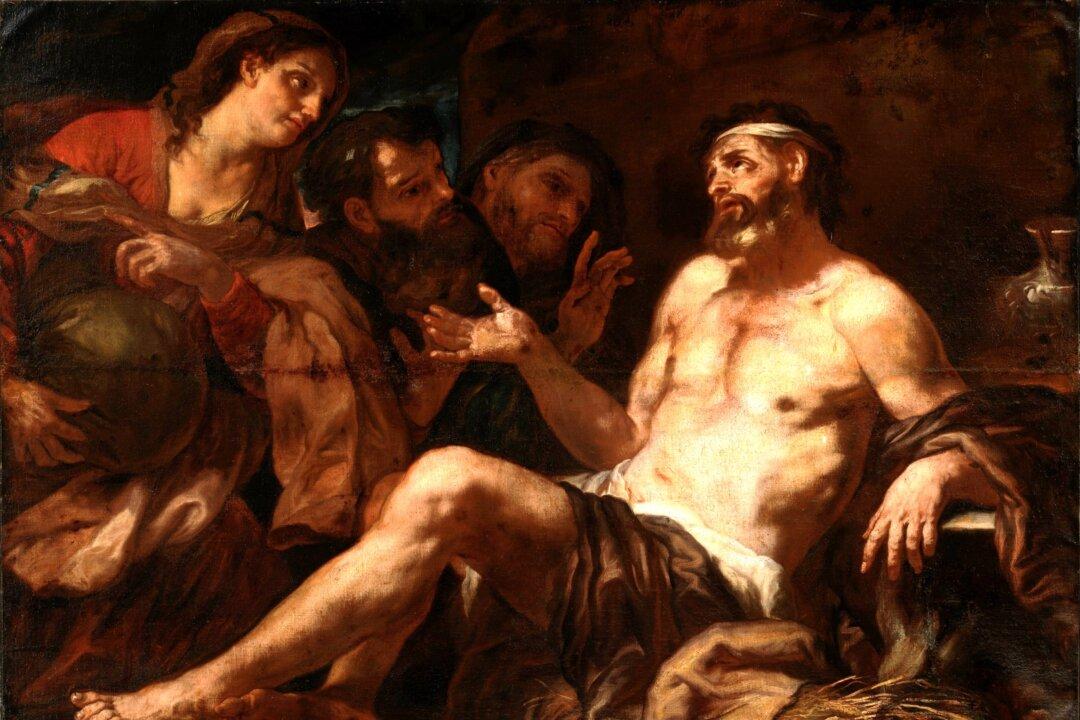

Poet Emma Lazarus, circa 1872. Public Domain