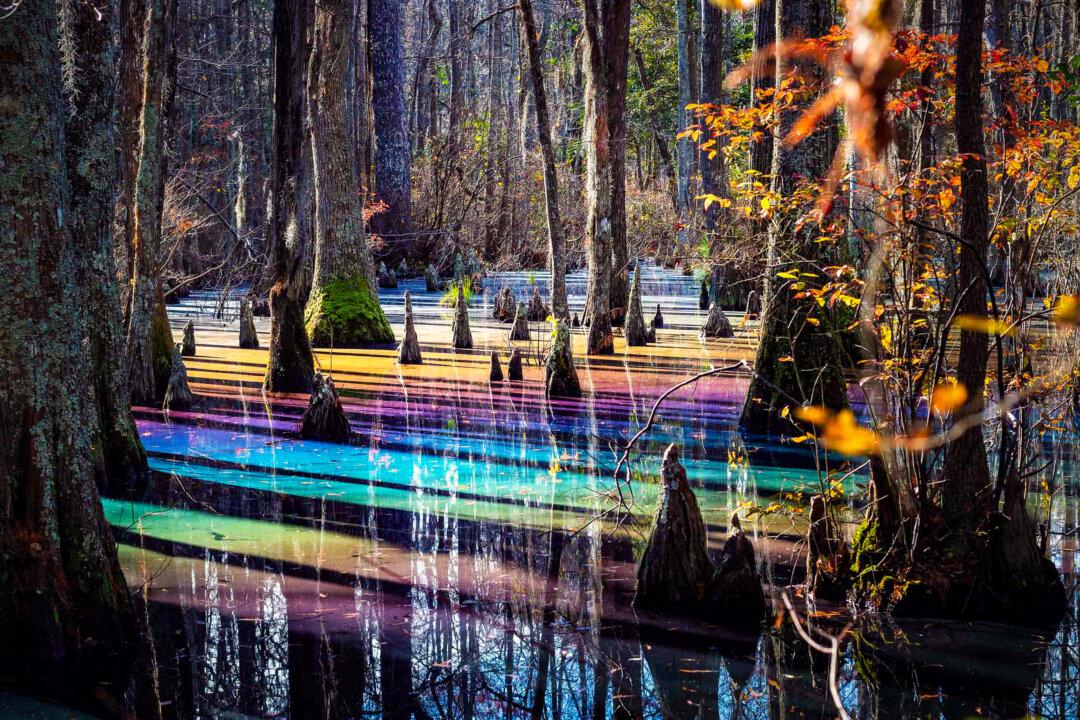

A vast untamed swampland once dominated from what is Virginia Beach today extending far inland, and history tells of emancipated slaves, free blacks, and outsider Europeans building free settlements on isolated islands deep in the dismal mire.

Legends and history abound in these “foul damps,” as early Virginian explorer William Byrd II called them, which “ascent without ceasing, corrupt the air, and render it unfit for respiration”—legends including even the English pirate Blackbeard, who hid in the marsh during the War of 1812. The interior waterways were later used by patrols of both the North and South during the Civil War.