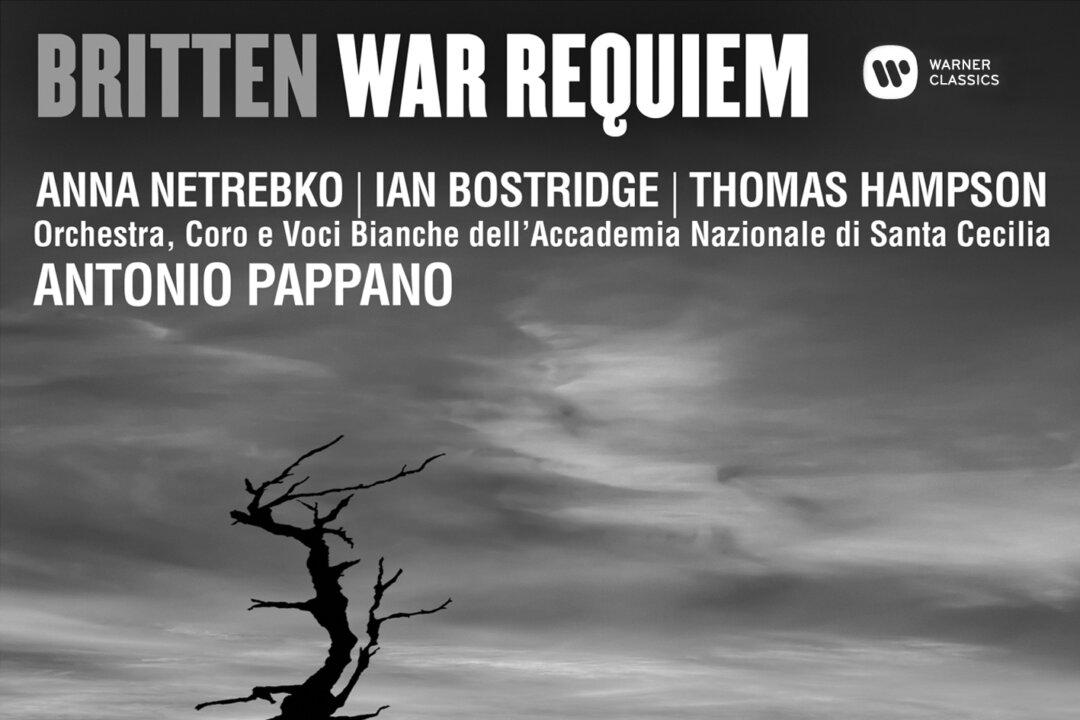

To honor what would have been English composer Benjamin Britten’s 100th

birthday—he died in 1976—Warner Classics released a magnificent new

recording of his “War Requiem.”

Britten was a pacifist and he had considered writing an oratorio about the

horrors that had occurred during the first half of the 20th century,

including the devastation of World War II, the bombings of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki, and the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi.

These ideas gestated over a period of years, during which he completed

operas and other works. In 1958, Britten was asked to write a piece to

commemorate the consecration of a cathedral that was being built in

Coventry, England.

The church in that city had been standing since the 15th century but was

destroyed during a bombing by the German air force in 1940.

The composer conceived a large scale work for chorus, orchestra, and

soloists. It was written, in Britten’s words, “in memory of those of all

nations who died in the last war.” He decided to mix the Latin text with

poems by Wilfred Owen, the English poet who died in the trenches during

World War I. Ironically, the war ended one week after he was killed.

Britten quoted Owen on the title page: “My subject is War, and the pity of

War. / The Poetry is in the pity ... / All a poet can do today is warn.”

To convey the universality, for the debut performance, Britten chose

soloists from three countries that fought in World War II: Russian soprano

Galina Vishnevskaya, English tenor Peter Pears, and German baritone Dietrich

Fischer-Dieskau (who had been drafted into the German army and spent two

years as a prisoner of war by the American forces).

The Soviet government wouldn’t allow Vishnevskaya to appear at the work’s

premiere in 1962, though she was allowed to take part in the recording the

following year. Because she told the composer she could not sing in English,

he had her perform the Latin texts.

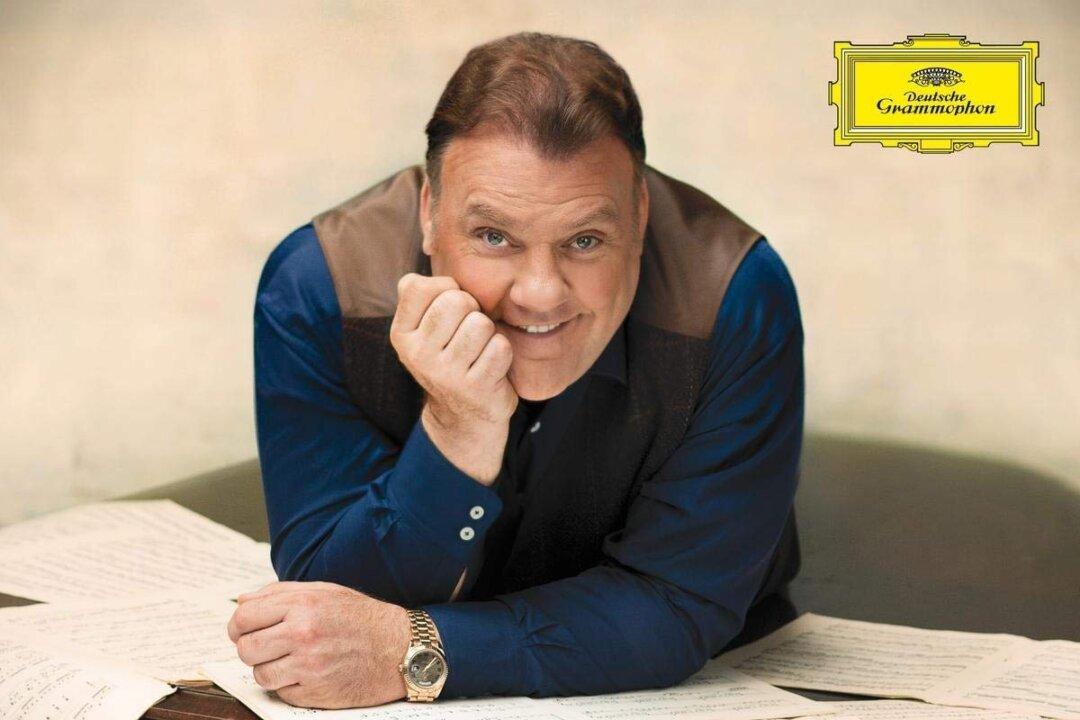

The new recording features soprano Anna Netrebko, tenor Ian Bostridge, and

baritone Thomas Hampson with the Orchestra and Chorus of the Accademia

Nazionale di Santa Cecilia conducted by Sir Antonio Pappano. Again, there is

a Russian soprano and an English tenor but the baritone is an American

rather than a German.

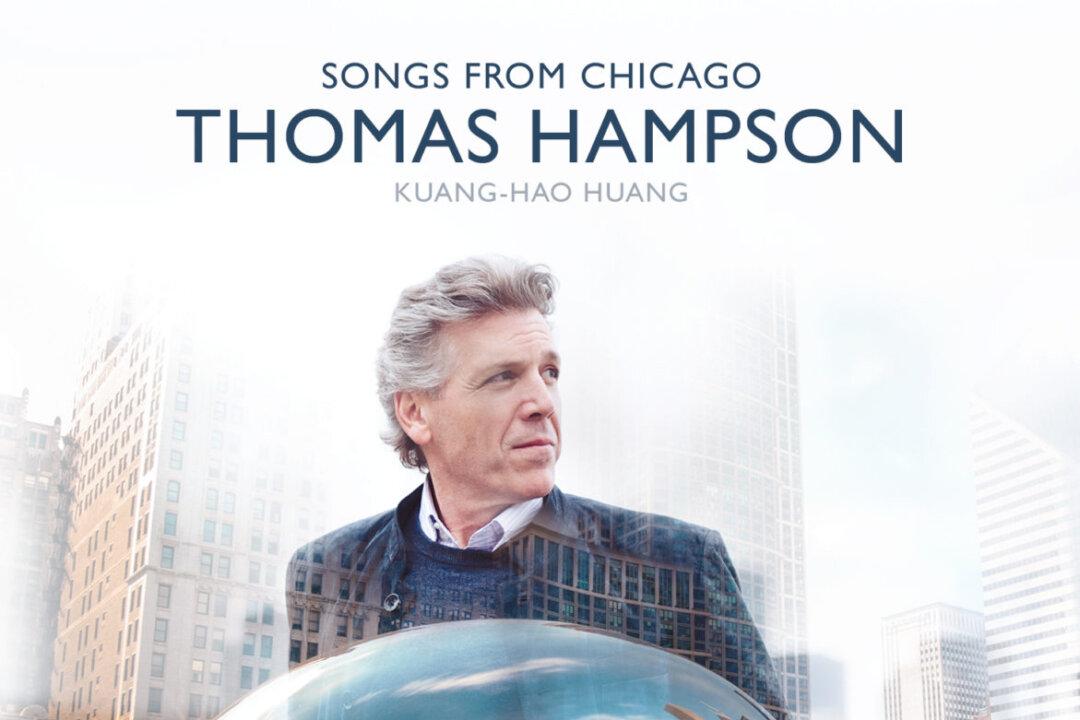

The recording stands up to the original. All three sing sensitively, with

Hampson superior to Fischer-Dieskau in the projection of Owen’s poetry.

Bostridge produces a bell-like tone making the more lyrical portions sound

even more eerie—he is at home with Britten’s music and coincidentally

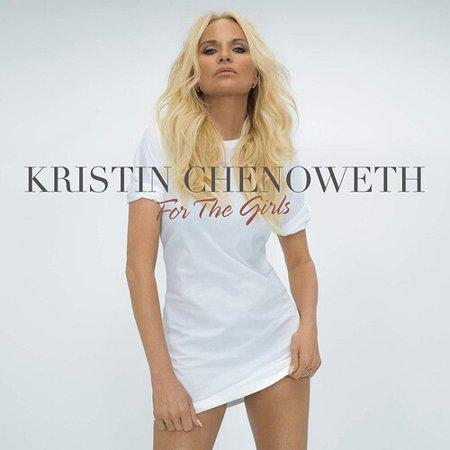

recorded the composer’s songs with Pappano playing piano. Netrebko is a

powerhouse, matching Vishnevskaya in dramatic force.

The sound quality is exceptionally clear. Whether the chorus is singing

about the “day of wrath,” the soprano and chorus are begging the “fount of

pity” to save them, the baritone is contemplating “the great gun towering

toward Heaven,” or the tenor is singing of the “passing bells for those who

die as cattle,” the effect is one of absolute horror at war’s devastation.

Unfortunately, the tragic work is as timely today as when it was written.

Netrebko is currently appearing at the Metropolitan Opera in Donizetti’s

comic opera, “L’Elisir d’Amore” (until Feb. 1) and Hampson will be appearing

there in Berg’s tragic opera “Wozzeck” (March 6–22).