The future of British luxury watchmaking can be found in the past via award-winning Struthers Watchmakers. The Struthers ethos is to use the best watchmaking in the world from the pre-1960s—the same traditional materials, methods, and tools of the past—to literally remake history in their one-of-a-kind timepieces.

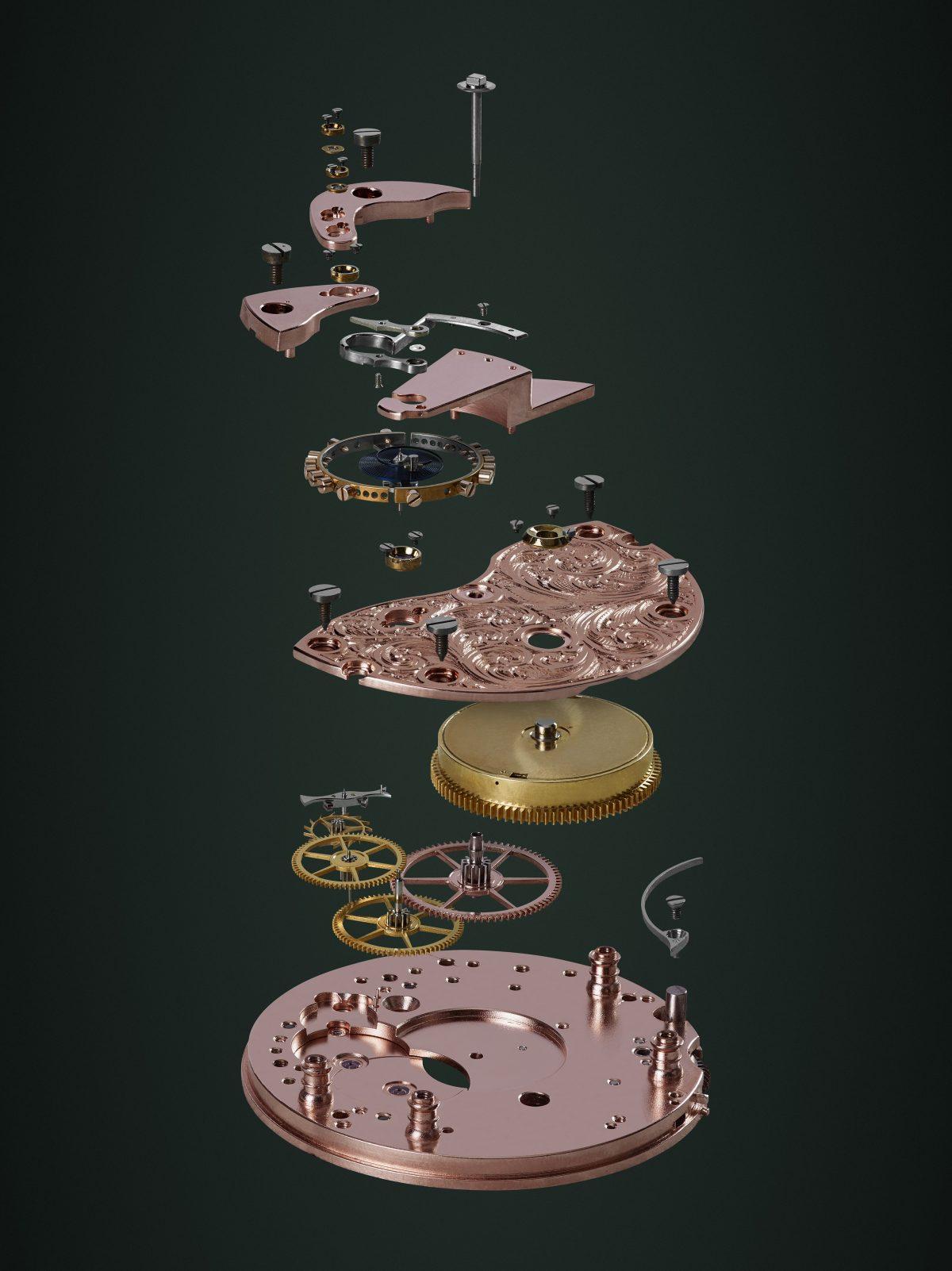

Pieces of "The Carter," pocket watch by Struthers Watchmakers. Jonny Wilson