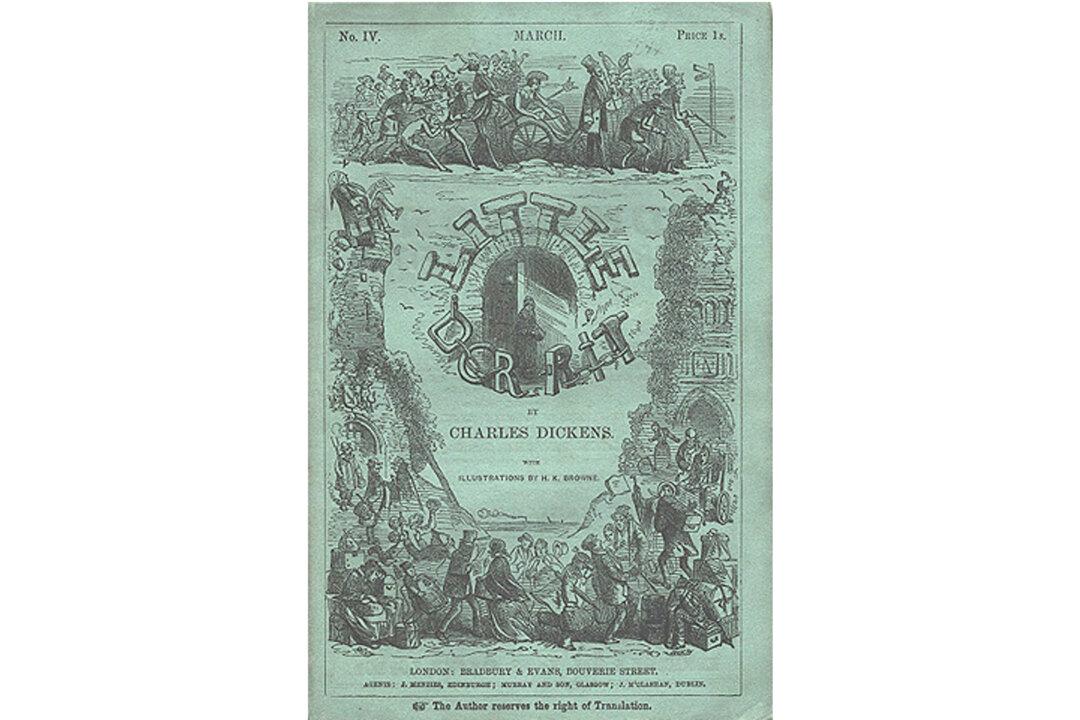

The great 19th-century novelist Charles Dickens possessed a distinct genius for portraying innocence and goodness with resplendent attractiveness. From little Davie in “David Copperfield” to Esther Summerson in “Bleak House” to Amy Dorrit in “Little Dorrit,” Dickens offers readers humble and innocent characters that help them believe that goodness can be found in humanity.

Skeptical modern critics accuse Dickens of crafting unrealistically virtuous characters, arguing that, in effect, that no one is really like that, no one is that perfect. Anne Stevenson, for example, writes that “on any other terms than those of allegory, angelic Amy would be squirmingly hard to swallow.” But this accusation is unfair. While such shining souls are rare, we do encounter them from time to time. Dickens’s characters remind us of that truth. They present us with inspiration for our own struggles, and show us how to persevere in the midst of hard times by clinging to the good and the true.