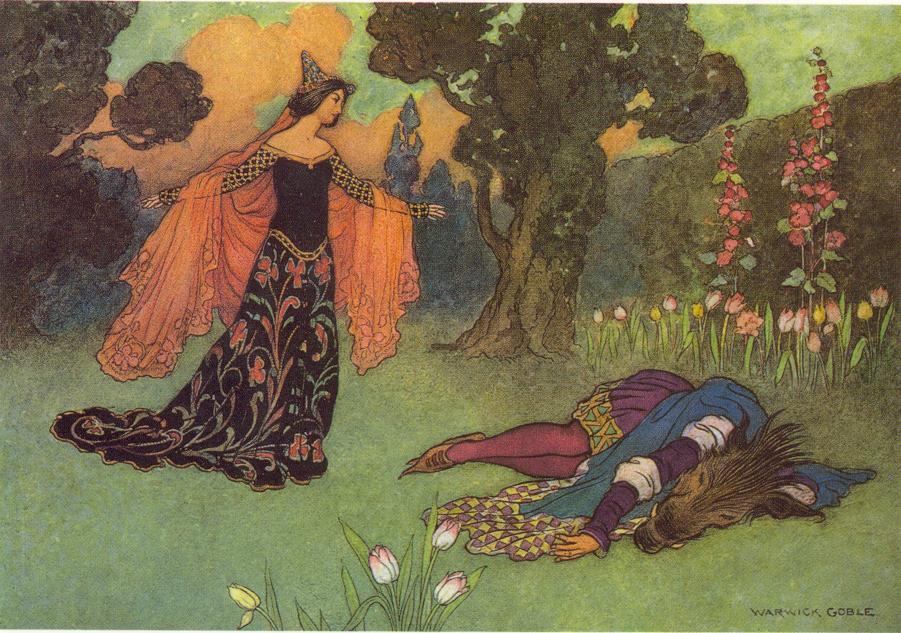

Did you know that fairy tales like “Beauty and the Beast,” “Rumpelstiltskin,” and “The Smith and the Devil” may have originated 4,000 to 6,000 years ago? Scholars think so.

One fairy tale researcher, Dr. Jamie Tehrani, says that these stories “have been told since before even English, French, and Italian existed. They were probably told in an extinct Indo-European language.” Yet they’re still enchanting children today. And the modern incarnation of the fairy tale—the genre of fantasy fiction—has become a behemoth in the world of contemporary literature, for children and adults alike.