Last week, The Australian reported that 49 artworks had been identified by the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA) with gaps in their ownership history that could signal they were stolen.

Asian antiquities account for 24 of the potentially problematic pieces. The other 25 have missing ownership information from the early 1930s to 1945, during Nazi-era Europe.

After a great deal of negotiation and protests from descendants of Jewish families whose art works, as well as countries such as Israel and European countries which had important items stolen by the Nazis, European museums have had to scour their records and publicise them where there appear to be gaps in the history of provenance.

This case is, alas, only the tip of the iceberg. The Australian reported last Thursday that the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW) paid A$300,000 in 2002 to acquire:

a stone carving of Shiva with Nandi … with a bogus ownership history documents from dealer Subhash Kapoor.

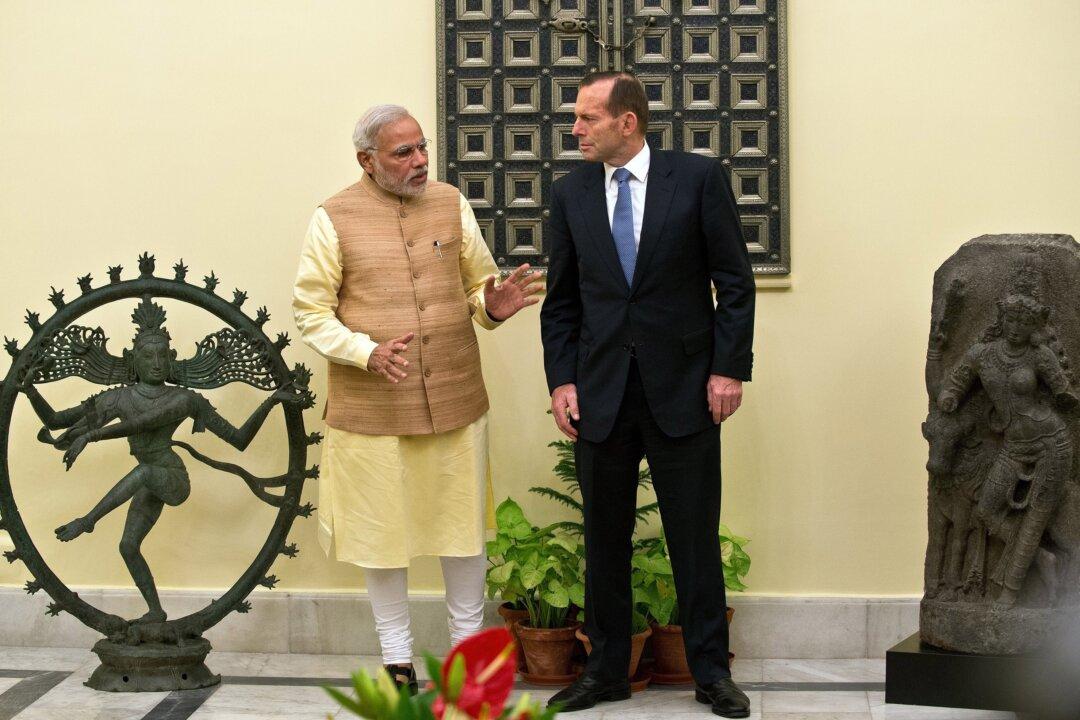

In September the Australian Prime Minister personally returned a 900-year-old bronze Dancing Shiva (Shiva Nataraja) to the Prime Minister of India which had been bought by the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) and was subsequently found to have been stolen from a temple in southern India.

In a country which has been a party to the Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property - 1970 since 1989, how did the AGSA, the NGA and the AGNSW find themselves in such egregious situations?

Despite the passage of the Protection of Movable Cultural Heritage Act 1986 which implements for Australia the provisions of the 1970 Convention, the holding institutions have not undertaken the effort that they should have over the last 25 years.

Dancing Shiva

The Dancing Shiva saga was the result of an international investigation of an idol-smuggling operation involving an Indian dealer selling cultural objects of very high quality in the international market.

New York-based art dealer Subhash Kapoor was arrested on an Interpol red notice and held in Germany while a wide investigation was undertaken also in the United States. Kapoor was then extradited to India for prosecution there.

The problem of stolen cultural objects from countries with rich and cherished heritage objects has been serious for many countries – Afghanistan, Cambodia, China, Greece, Guatemala, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Thailand, Turkey and many others – has been a point of contention for centuries.

Some objects were taken in “punitive raids” or colonial occupation and others in post-colonial transactions through bribery, theft and other forms of persuasion.