‘Beauty is truth, truth beauty,’—that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. —John Keats, “Ode on a Grecian Urn”

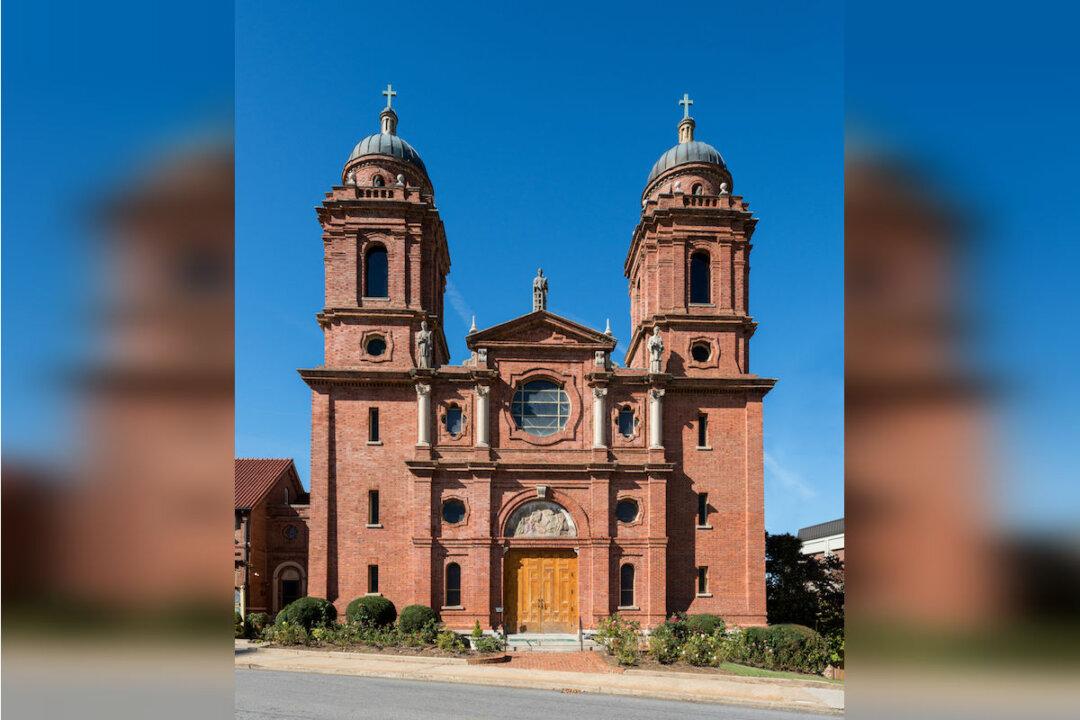

When you enter the vestibule of the Basilica of Saint Lawrence, Deacon and Martyr, you’ll pass a sign reading “Reverential Quiet Please.”Outside the walls of this church are the streets of Asheville, North Carolina. These streets and sidewalks swarm with tourists, locals, hippies, jugglers, guitar players, beggars, and the tattooed and dreadlocked crowd, a stew of humanity that almost 20 years ago inspired Rolling Stone Magazine to dub Asheville “the new freak capital of the U.S.”