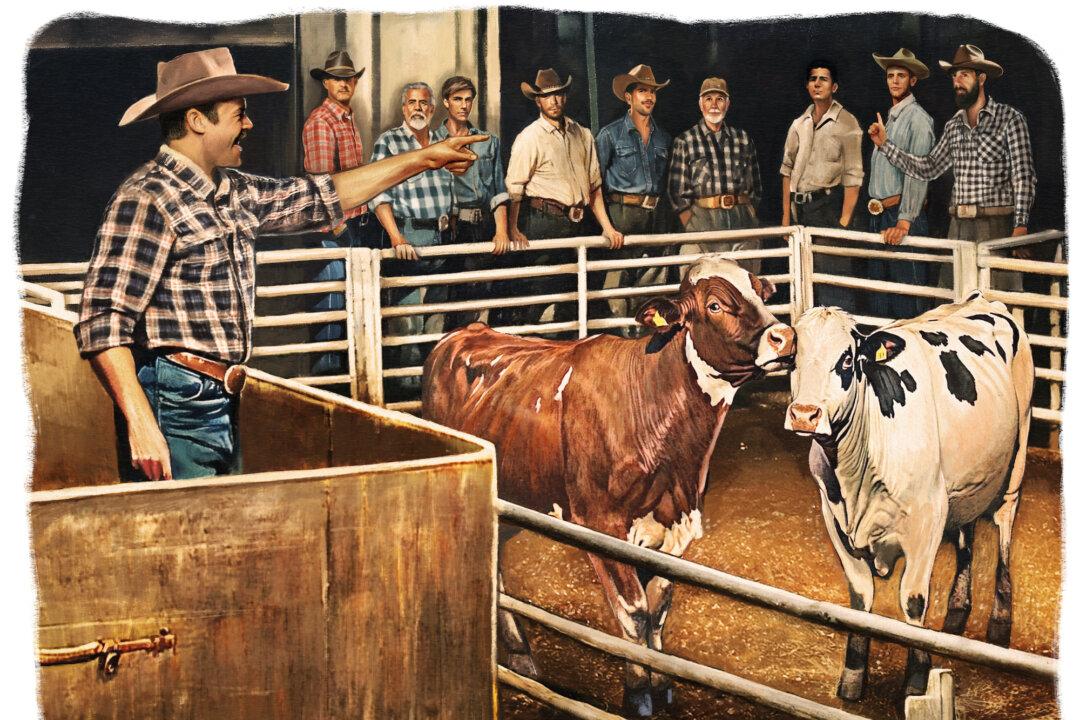

Going to a cattle auction isn’t most people’s idea of a weekend outing. But maybe it should be.

Much can be gleaned from a deeper awareness of how agriculture sustains us and ties us to the past. This agricultural structure supports civilization and constantly surrounds us, but fewer people than ever in human history have direct contact with the production and distribution of food. Therefore, they don’t know what it all means. Nor do they understand its implications for how they live.