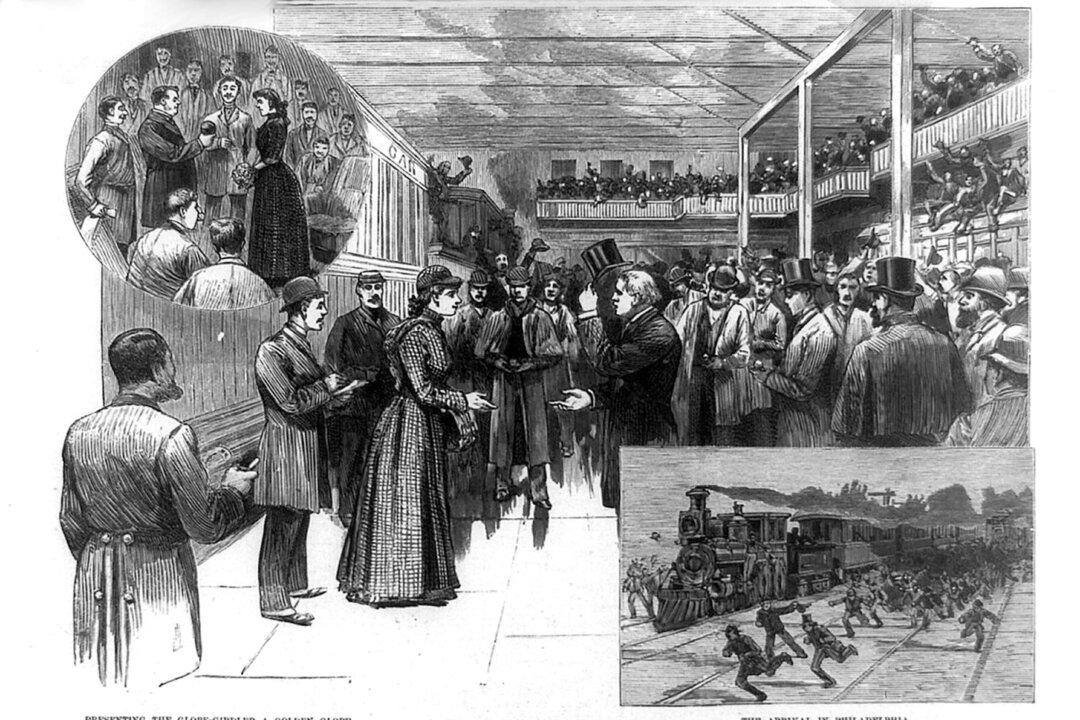

In 1872, the Daily Telegraph calculated that, by way of steamboats and railroads, the world could be traversed in 80 days. The idea was tempting enough that Phileas Fogg wagered 20,000 pounds he could do it. Fogg was the protagonist in the Jules Verne novel “Around the World in Eighty Days,” and, although Fogg was fictional, the calculation was not.

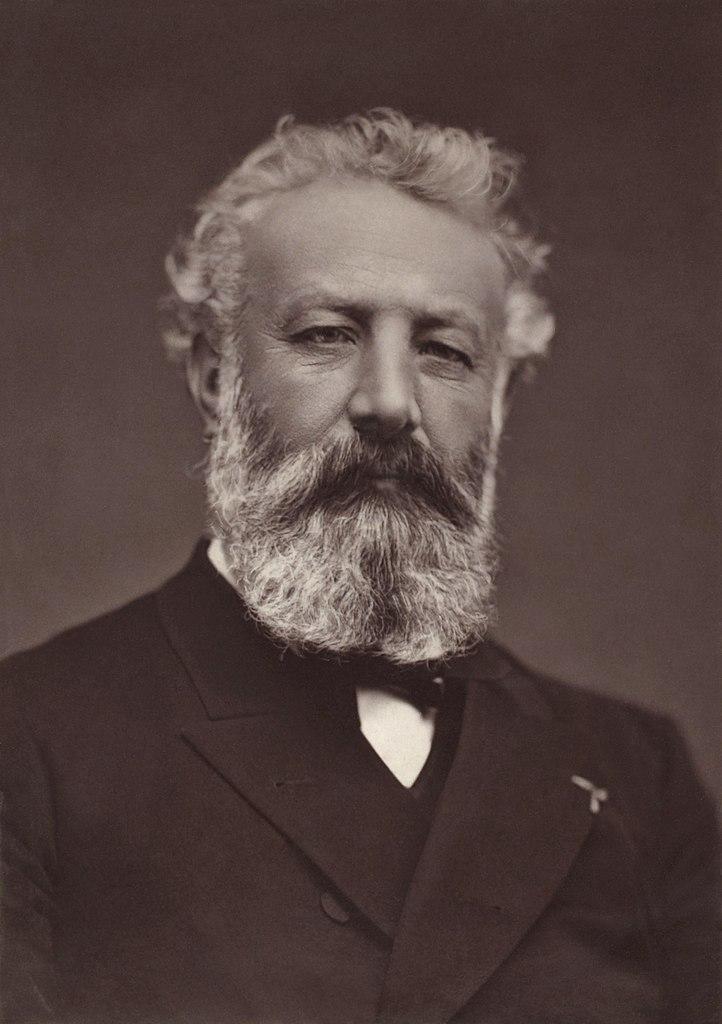

A photo portrait of Jules Verne, 1884, by Étienne Carjat. PD-US