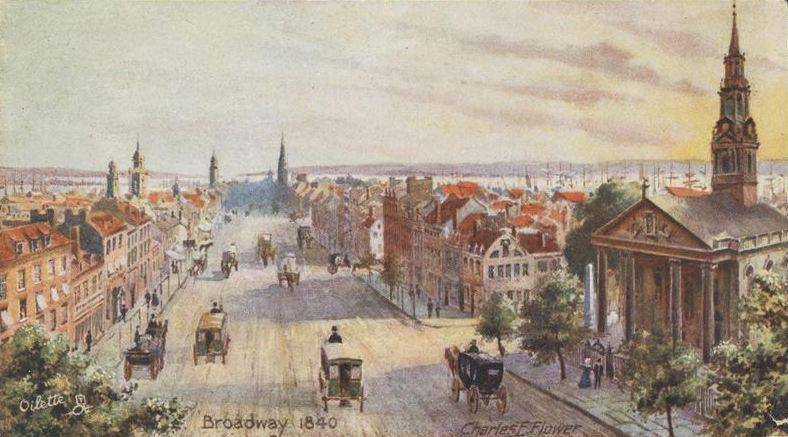

St. Paul’s Chapel in New York City is not just where George Washington prayed after being inaugurated as first President of the United States. It has been a place of worship for more than two and a half centuries, resulting in countless generations of congregants. But most noteworthy, it is a survivor of September 11, 2001. On that day, covered in the dust and debris of the unthinkable collapse of two skyscrapers, as well as the destruction of other surrounding buildings, St. Paul’s remained intact and resolute. In fact, it quickly became a refuge for anyone escaping the immediate horror raging beyond its walls. For almost a year afterward, impossible-to-determine numbers of rescue workers, volunteers, and victims’ friends and family members entered St. Paul’s to rest, reflect, cry, pray, and more.

Manhattan’s oldest surviving and continuously used church building, St. Paul’s Chapel was constructed in 1766 and named for Saul of Tarsus, a first-century persecutor of early Christians, whose name was changed to Paul when he was converted by Jesus on the road to Damascus—as is spelled out in Acts 9 of the Bible. Paul’s writings in Romans inspired 16th-century German protestant reformer, Martin Luther, so dramatically that he stood steadfastly in front of a Catholic tribunal to state his infamous position: “Here I stand. I can do no other.”