Civil rights champion Martin Luther King Jr. once said “Faith is taking the first step even when you don’t see the whole staircase.” This attitude became known as the “leap of faith,” which was first explained by the existentialist philosopher Soren Kierkegaard in the mid-1800s. For Kierkegaard, faith was an embrace of the world’s paradoxical complexities. This embrace is necessary to live a meaningful life, but it can only take place at the end of life’s three stages.

Soren Kierkegaard’s ‘Stages on Life’s Way’

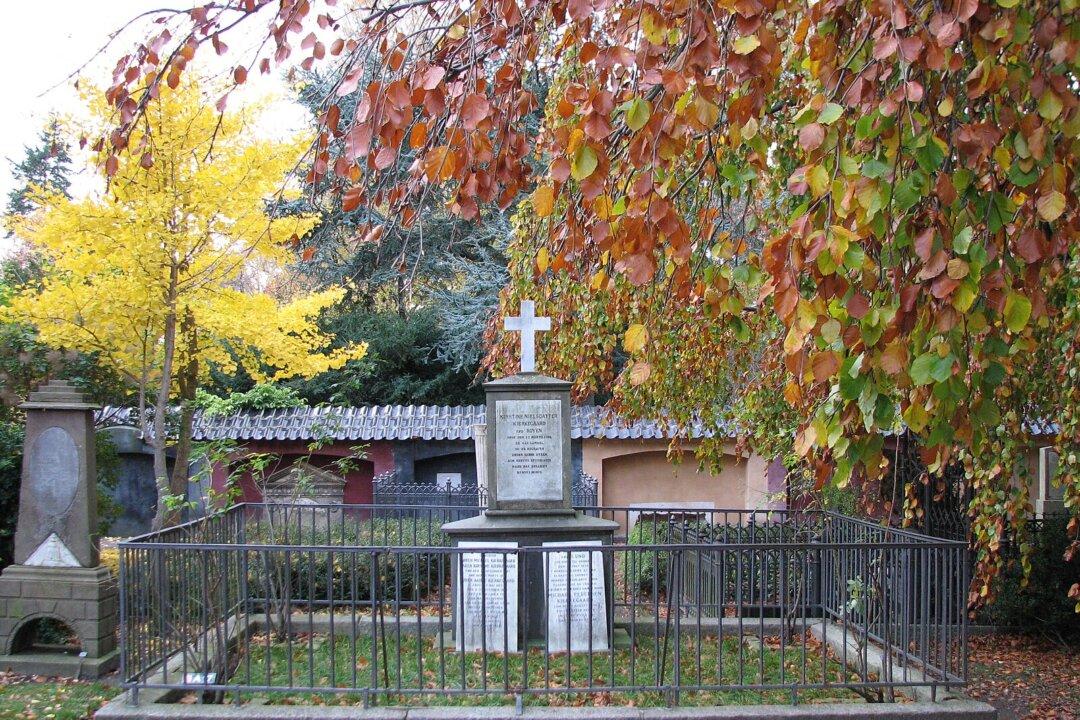

Born in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1813, Kierkegaard was the youngest of seven children. His family was wealthy and very religious. Young Kierkegaard studied theology, philosophy, and literature at the University of Copenhagen, but he never pursued a clerical or an academic career. He preferred the life of a solitary thinker.

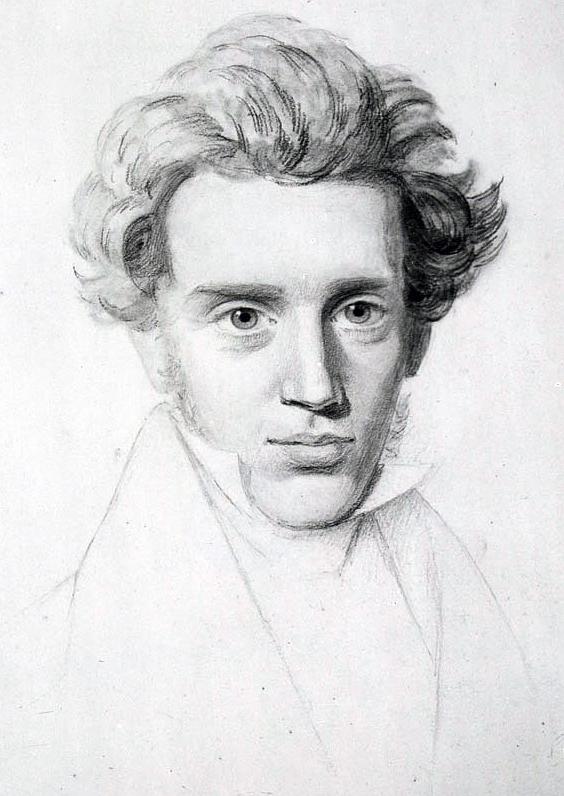

A Danish theologian, philosopher, and poet, Soren Kierkegaard wrote extensively on faith and religion. Public Domain