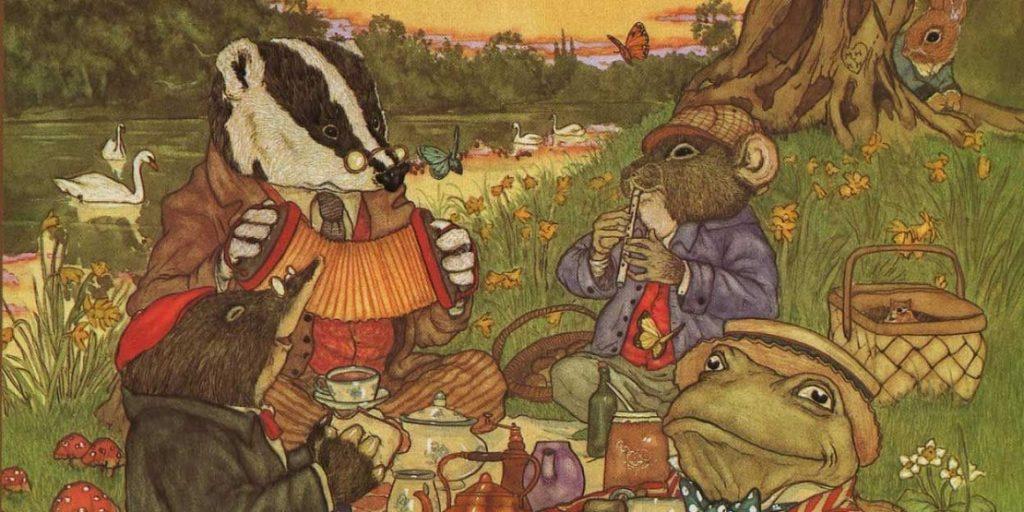

“The Wind in the Willows” is a glorious summer book that may be one of a kind in its ability to stir the soul to the joys of the good life.

Written by English author Kenneth Grahame in 1908, “The Wind in the Willows” is about the friendship of animals who represent, in a sense, types of people. Mole and Rat become friends after Mole runs from the doldrums of spring cleaning and discovers a river and a companionable Rat, a water vole who lives on the river and introduces him to this new expanse of the world.