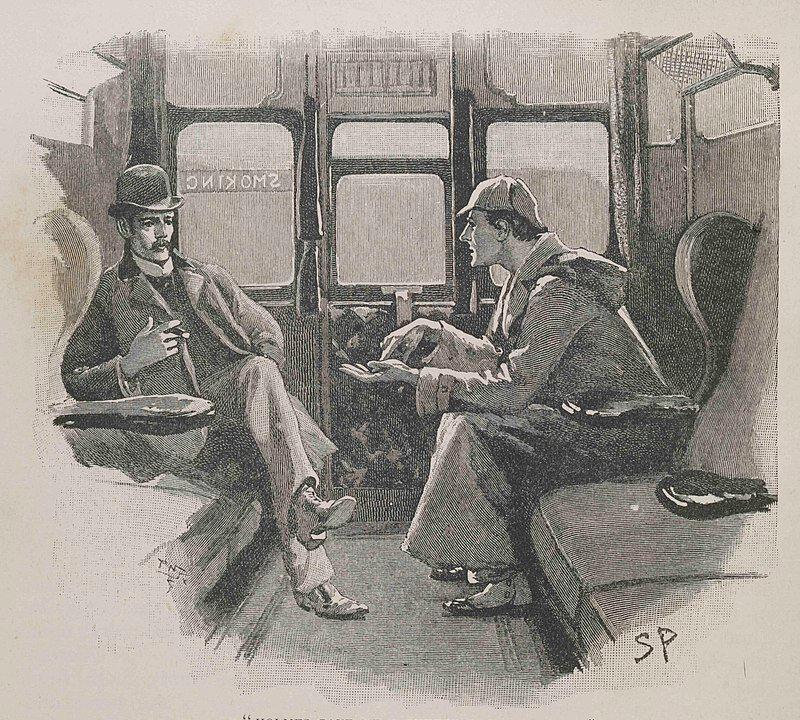

Among the lords of light literature, Sherlock Holmes towers. There is not much mystery about it, either. It is really quite “elementary, my dear Watson.”

“The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes,” published in 1892–93 in The Strand Magazine, by Arthur Conan Doyle is a collection of 12 remarkable cases in Mr. Holmes’s remarkable career. These include the nearest instance of the above popular misquote. “The Adventure of the Crooked Man” has the closest appearance of the “elementary” line in all of the 60 canonical Sherlock Holmes stories.