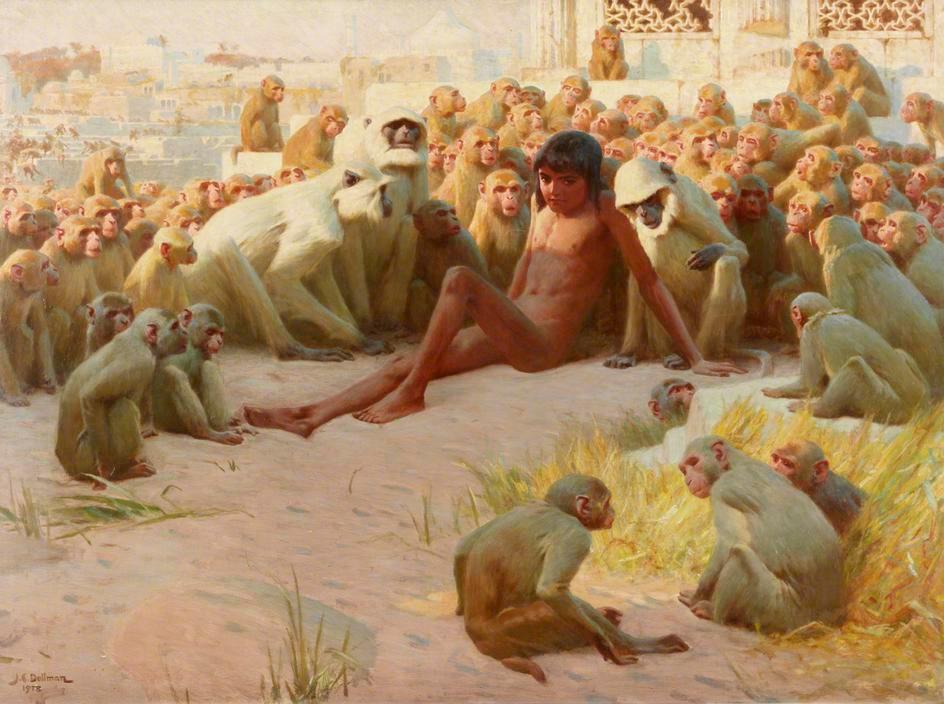

There are few books that encompass the soul of summertime, and “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer” is one of them. In it, the glorious line between romanticism and realism blurs in the haze of the summer sun.

No other book places dog-day youth on such a high and holy pedestal, stirring in every heart what was once young memories: those innocent escapades and rebellions when “all the summer world was bright and fresh, and brimming with life.” The golden green of a warm Saturday afternoon, the Eden of children, glows in the pages of this inimitable 1876 American classic.