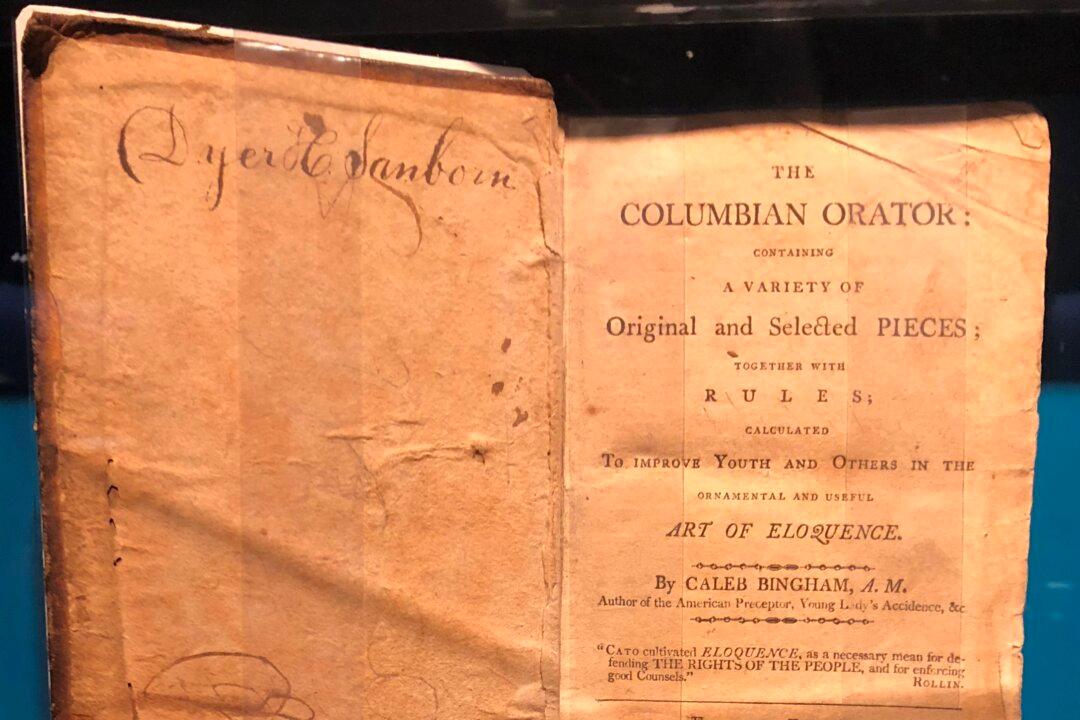

Though a history major in college and a disciple of Clio (the muse of history) ever since, I was unfamiliar with Caleb Bingham and his once famous compendium, “The Columbian Orator.”

After stumbling across an online article about Bingham’s book, I ordered a copy and received the historian and biographer David Blight’s edition of “The Columbian Orator: Containing a Variety of Original and Selected Pieces Together With Rules, Which Are Calculated to Improve Youth and Others, in the Ornamental and Useful Art of Eloquence.”