The ancient empire of the seafaring Phoenicians was built on two things: secrecy and snails.

Snails, Ships, and Caesars: Why Purple Is the Color of Royalty

The slimy origin of the color preferred by royalty is revealed.

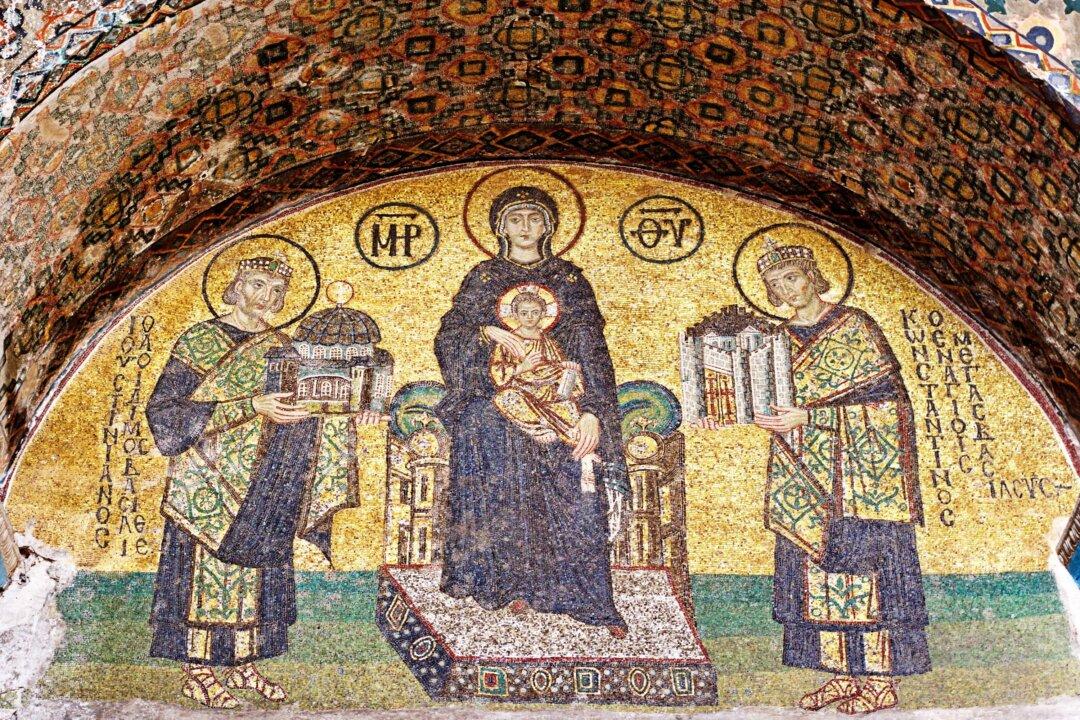

A Byzantine mosaic of Constantine the Great and Emperor Justinian I presenting Constantinople and St. Sophia Basilica to the Virgin Mary (holding the Christ Child). All three figures are adorned with Tyrian purple robes. Faraways/Shutterstock