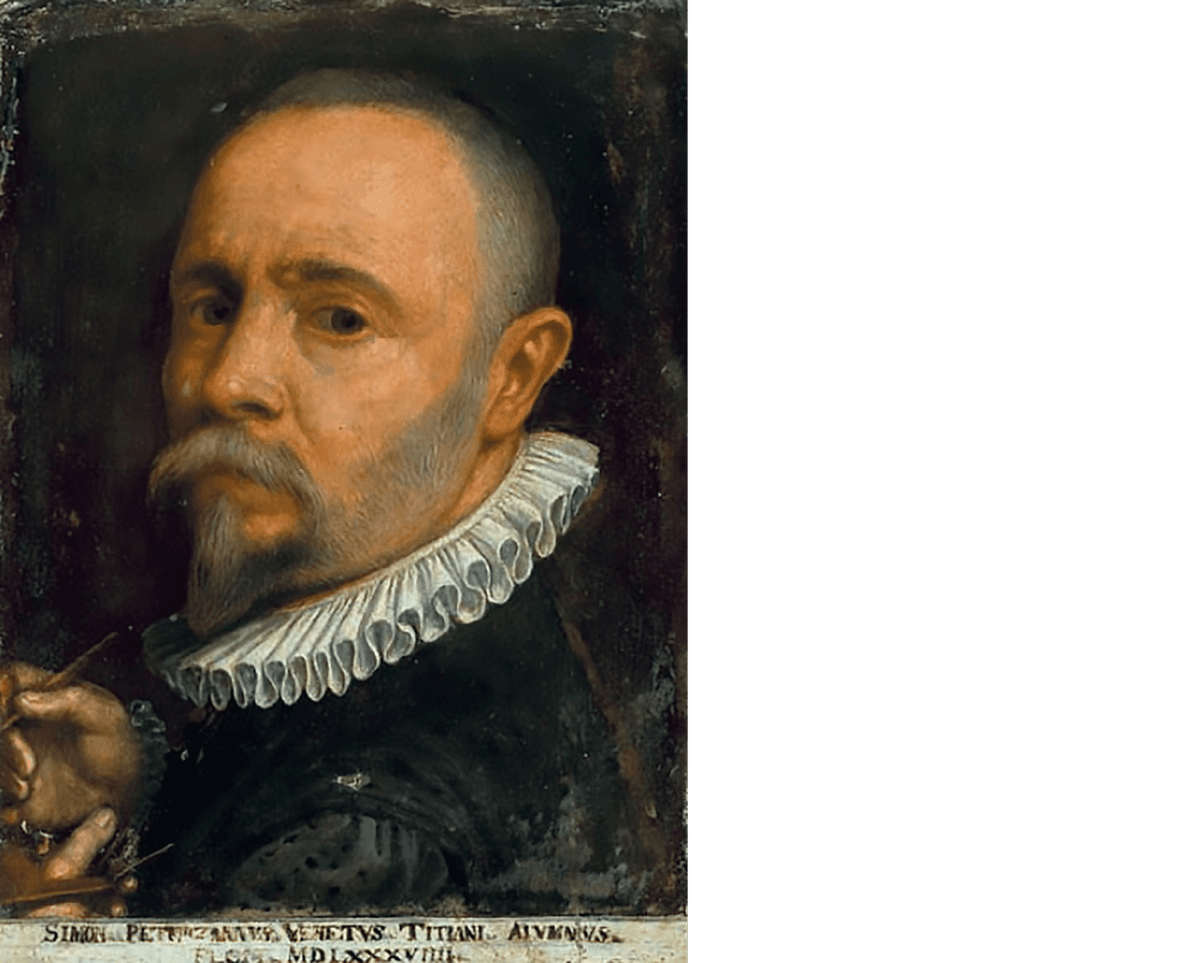

Except among some specialist art historians, Simone Peterzano is generally known only as the teacher of Caravaggio: the notable, great master of Baroque painting. Beyond that, he tends to be dismissed as a competent but unexceptional artist. On closer inspection, though, he becomes a fascinating example of how such artists can lay the foundations on which great masters build—a man who took some of the first steps toward the style that Caravaggio would one day perfect.

A self-portrait, 1589, by Simone Peterzano. Public Domain