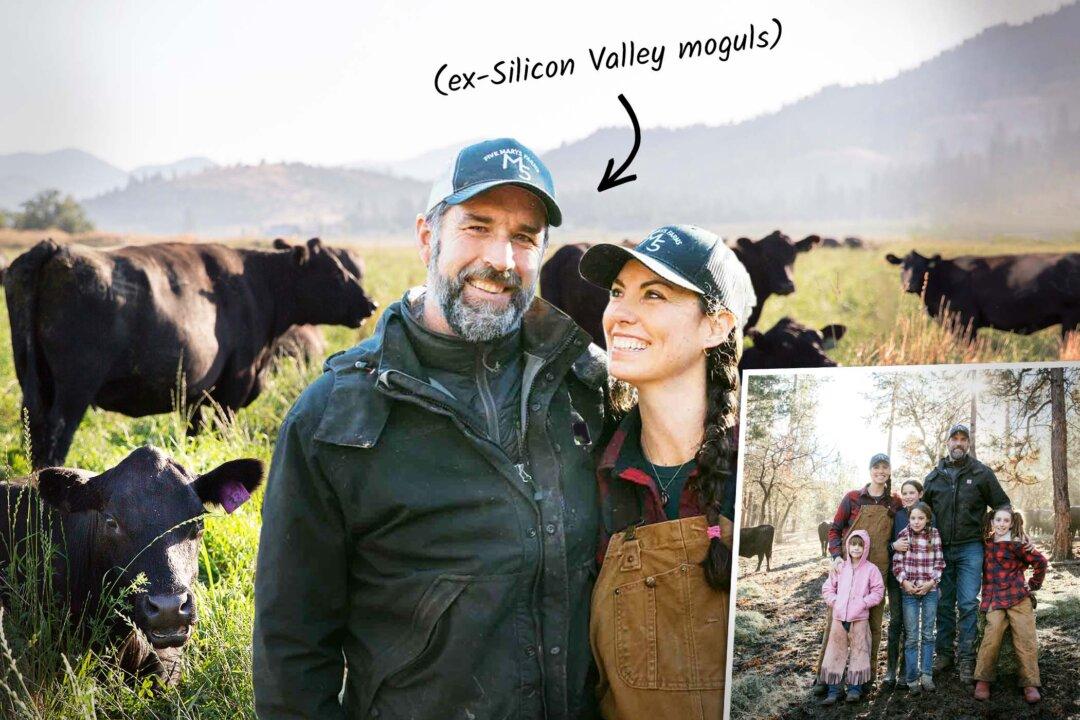

Ten years ago, Mary Heffernan got on her laptop and dug up the riskiest venture she and her husband had ever tackled. The couple were Silicon Valley entrepreneurs, but after finding land online, they made the gamble of a lifetime by taking up ranching in Northern California.

Today, they are first-generation ranchers. The catch? For the family, pastoral life is an endless field of risk. Yet it’s worth it, they say.