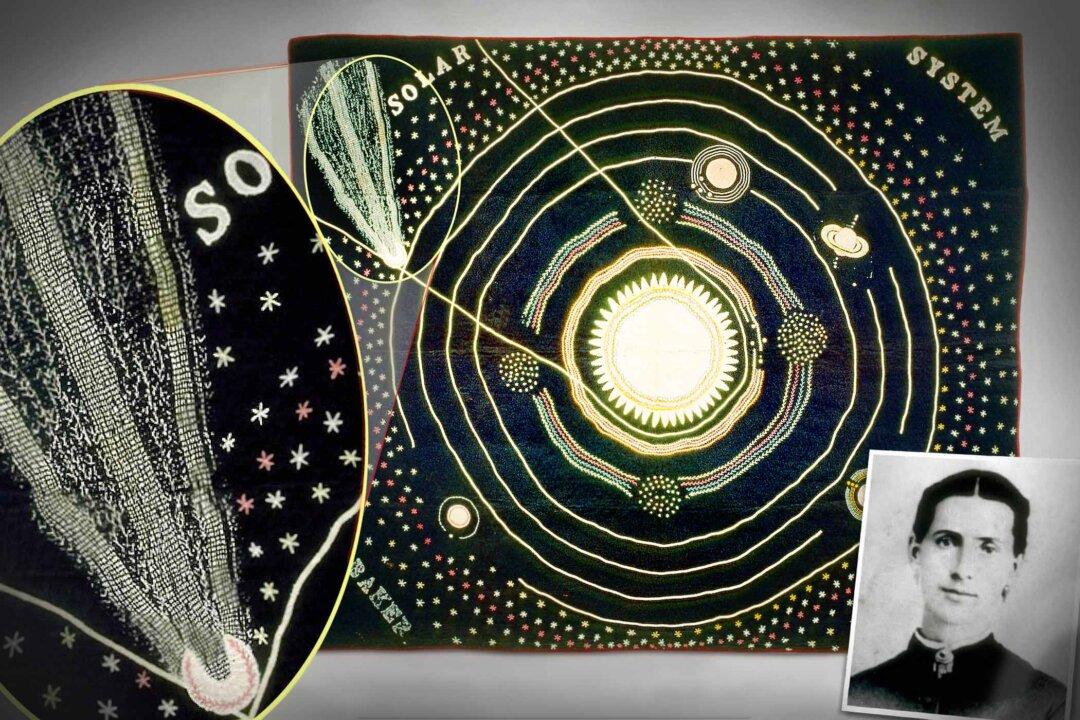

It’s as though their lives were woven together by the stars.

Though they mainly lived apart from each other—like the stars—the common thread of a comet’s discovery tied them together fortuitously.

It’s as though their lives were woven together by the stars.

Though they mainly lived apart from each other—like the stars—the common thread of a comet’s discovery tied them together fortuitously.