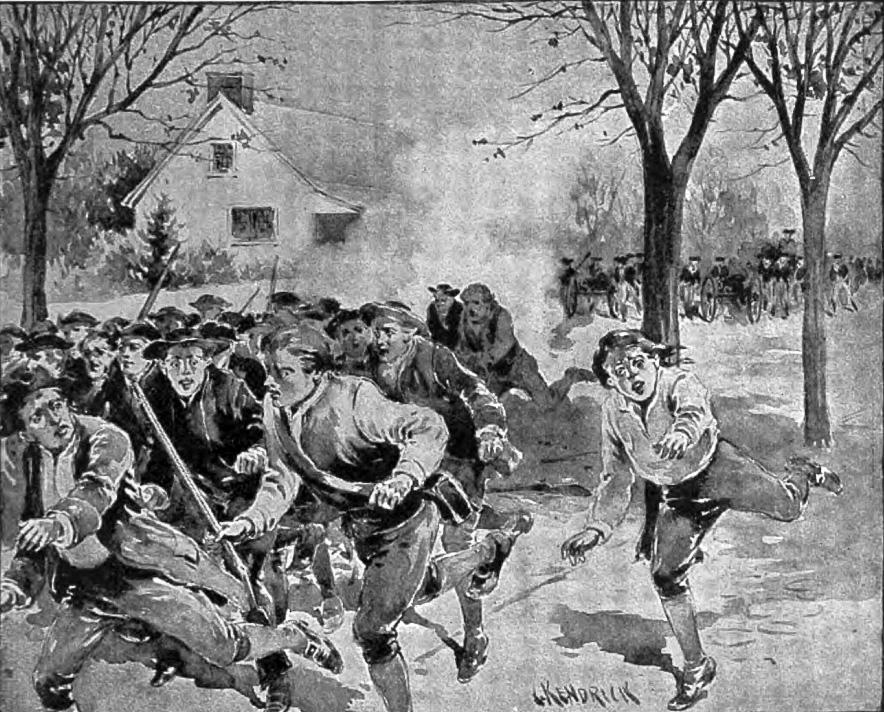

On May 16, 1771, approximately 3,500 men met at a large field in the Piedmont region of North Carolina. For about two decades, the fight over excessive taxation and political corruption had increased from debate to protests to rioting. Now, it was an armed struggle. Of the 3,500 men who met near Great Alamance Creek, 2,000 were citizen farmers called Regulators. The others—slightly outnumbered, but better armed and better organized—were North Carolina militiamen. They had been sent by Governor James William Tryon to quell the rebellion.

Four months prior, on Jan. 15, Governor Tryon had signed the Johnston Act, which was “An Act for Preventing Tumultuous and Riotous Assemblies, and for the More Speedy and Effectually Punishing the Rioters, and for Restoring and Preserving the Public Peace of This Province.” What the Act did not do, obviously, was address the farmers’ grievances.