I sit in the dark, my back against the rough wooden wall of the barn, knees pulled in close in the cramped space, sweat running down my shoulders, trying to stifle the sound of my creaking stool. The air is stuffy and humid enough to swim in.

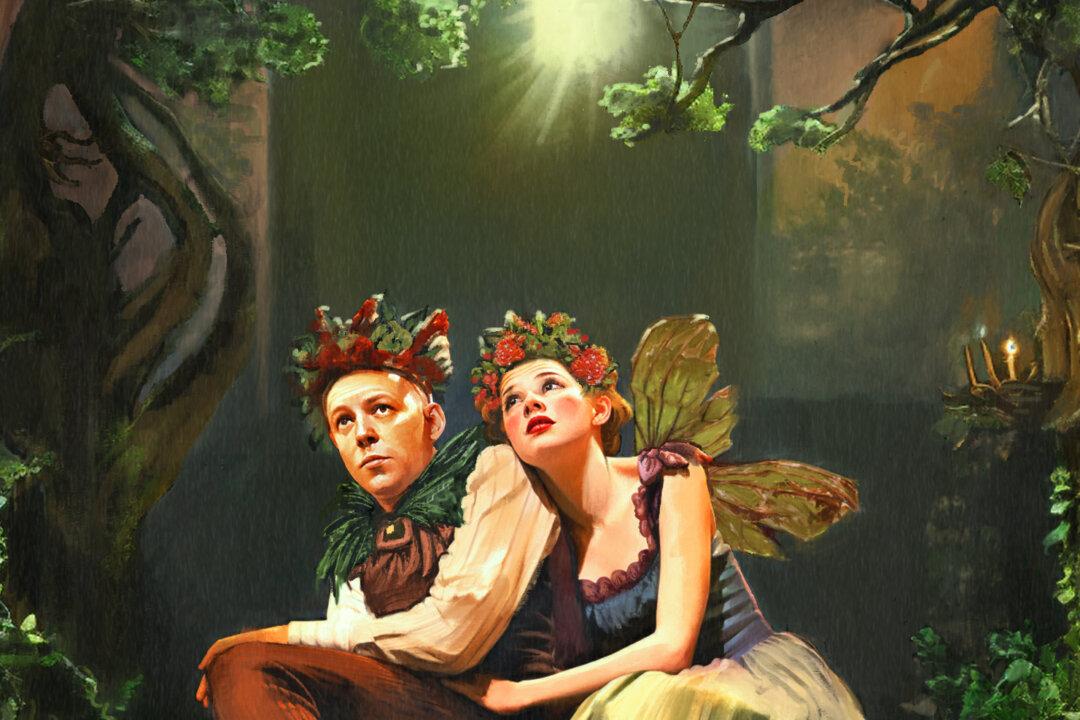

Through a seam between the planks of the stage wing, I can see the audience: a varied assembly of all ages, their faces bright and expectant, turned toward the light, their eyes riveted to the stage, which lies just a few feet from where I am concealed.