But little of Peter Shaffer’s Amadeus can be considered historically accurate. A. Peter Brown is a teacher at the School of Music at Indiana University. His article in The American Scholar Magazine says that composers Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Antonio Salieri were cordial toward each other. Moreover, Salieri had greater talent than the play “Amadeus” depicts, and Mozart was not the self-important “giggling, dirty-minded creature” that Shaffer’s Salieri describes him to be.

More likely, Shaffer has written a play to suit our modern sensibilities rather than to reveal truth about Mozart or Salieri. In fact, the play’s distortion of history may be even more timely in our reality TV let’s-eat-cockroaches-for-national-television world than it was in the 1980s when Shaffer wrote the play. Director Gary Griffin’s Amadeus is certainly in keeping with our current sensibilities.

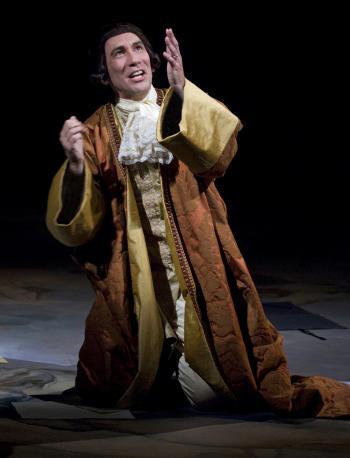

Antonio Salieri (Robert Sella) narrates the entire play as a reflective aside on the day of his death in 1781. He takes us to the time when Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Robbie Collier Sublett), a young upstart composer, has just arrived in Vienna. Salieri has worked hard to make his way into the court’s favor and gain his position of power.

Salieri, a vain and pompous small-town boy who is now the court composer to Joseph II, Emperor of Austria, cannot accept the brilliance of the newcomer. Salieri would have us believe that his story is about his war with God. He decides God has forsaken him for Mozart—hence the title of the play.

At the end of the first act, he bitterly renounces God and declares war on Mozart, believing that if he destroys Mozart, he can regain God’s favor. He proceeds to crush Mozart, using his position of power at court to undermine Mozart’s success, driving him and his wife to penury and ultimately an early death.

On his deathbed, Mozart accuses Salieri of “poisoning” him, and Salieri picks up that idea in later life to push his celebrity status because he cannot bear that Mozart has become even more famous in death than in life. He sees this exaggeration of the truth as his ticket out of mediocrity.

Robert Sella, as Salieri, is on stage for the entire performance, either stage front re-enacting events or in the background watching the events unfold. Sella introduces all the characters with snide facial expressions and sarcastic barbs. As the young Salieri, he has energy to spare as he flashes from scene to scene, carrying us further into his “madness.” As the old man about to die and demonized by his own admission as the murderer of Mozart, he displays a gleam in his eye.

In the end, Salieri tries to kill himself by cutting his own throat. He fails to die and lives another three years. The stunned look Sella gives the audience when this is announced is priceless.

The staging is minimal—a couple of chairs and a table that is used in many scenes as either a banquet table at court or a writing desk at Mozart’s house. The staging allows an openness which pulls you into the play, especially since Salieri is talking to the audience for most of the performance. The characters have more space to move about and therefore are allowed more room to be elaborate and grandiose in their 18th century court gestures.

The only prop that never moves is the piano in the corner. Although the actors only actually touch the piano once, in the first act, it nonetheless serves to remind the audience that this is a battle between composers.