SALLASAW, Okla.—Of the Native Americans historically noted, Sequoyah is less known. Yet Sequoyah’s contribution to the Cherokee people is so significant that his log home, nestled in the rolling hills near rural Sallisaw, Oklahoma, has been preserved so that travelers can jump off transcontinental Interstate 40 going east or west and learn about how he created a written language for his people.

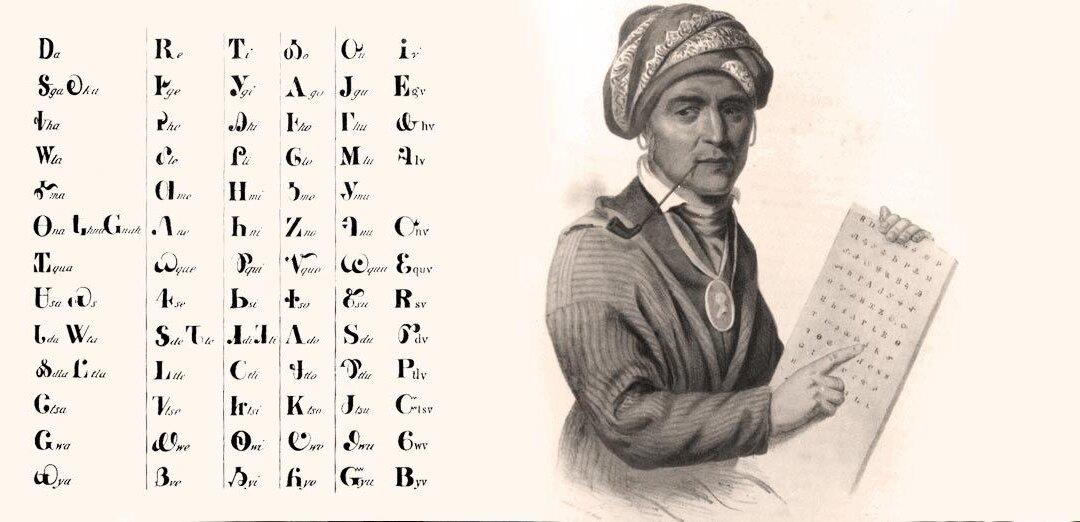

Since I lived for the last eight years in the Western North Carolina mountains, near the Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indian’s Qualla Boundary, I knew about Sequoyah and his syllabary, a written form of syllables to convey his native people’s language. In fact, driving through the territory established for Cherokee in the Appalachian Mountains after the Indian Removal Act of 1830, I have always admired the unique shapes and forms accompanying English words on road signs, businesses, and more. Even educational roadside signs pertaining to Cherokee history feature words bearing distinct 86 symbols.