Scientists in Japan appear to be intent on solving Zen riddles. A tree that falls in the forest when no one is around to hear it does indeed make a sound—or rather, a smell.

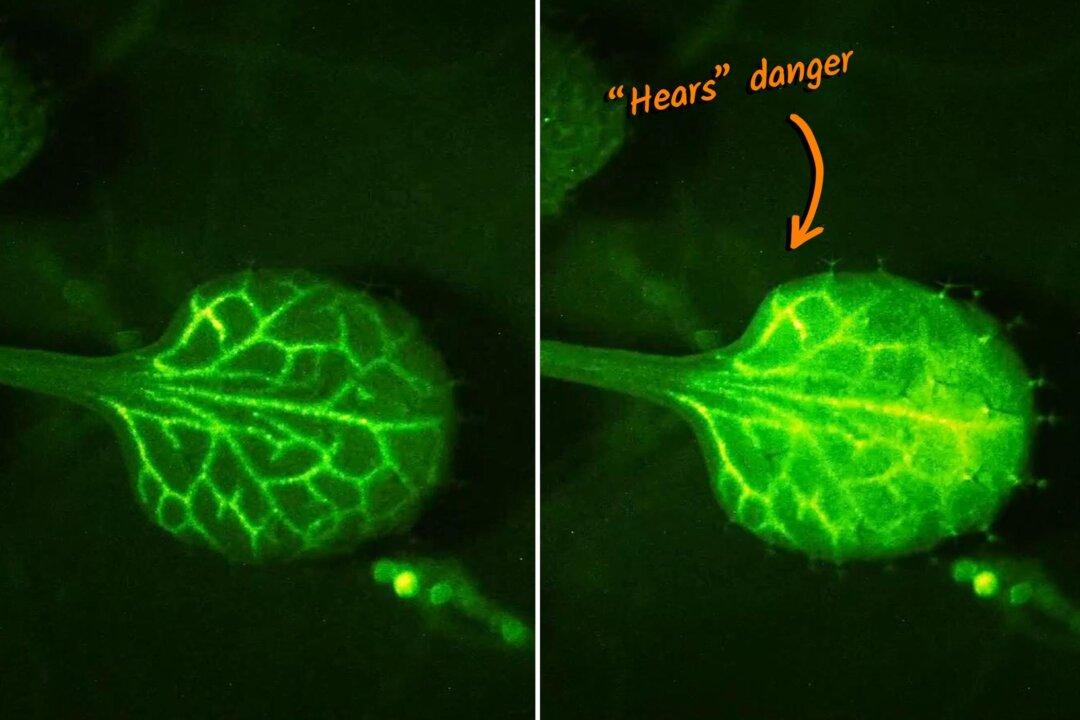

By probing deeper into the hidden ways that plants communicate, researchers at Saitama University have visually witnessed the transmission and reception of “warning” signals from stressed and injured plants to their neighbors. Within seconds of being wounded, they emit a fine mist of airborne compounds, signaling for other plants to raise their defenses.