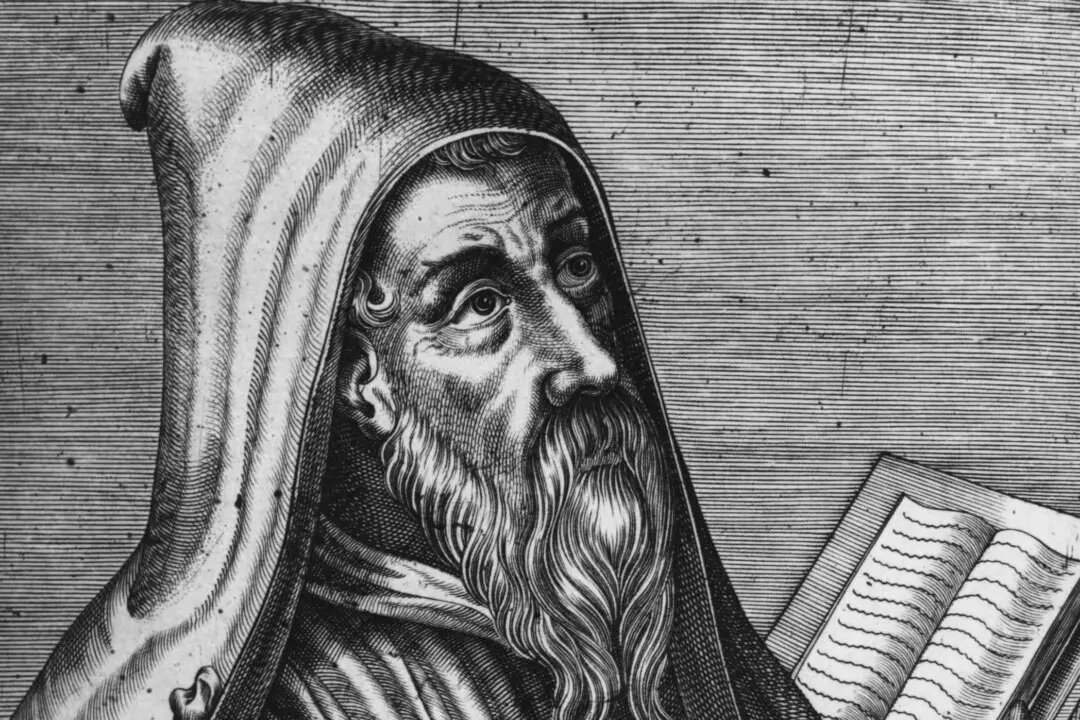

When 16-year-old Saint Augustine of Hippo stole and ate a handful of pears from his neighbor’s orchard, he felt a nagging remorse. In his “Confessions,” he wondered why he stole food even though he wasn’t hungry. He concluded that no one desires evil for evil’s sake. Rather, we desire lesser, immediately gratifying goods over greater ones. This insight into the nature of sin prompted the reflections that later became his most famous work.

British academic and theologian Henry Chadwick described the “Confessions” as one of “the great masterpieces of western literature.” After a series of candid reflections on his youth, the book traces Augustine’s struggles with sin and paganism in adulthood. Augustine’s progression from sin to virtue is clear through three stages of his relationship to language, which, as he eventually discovered, was the same as his relationship to God.