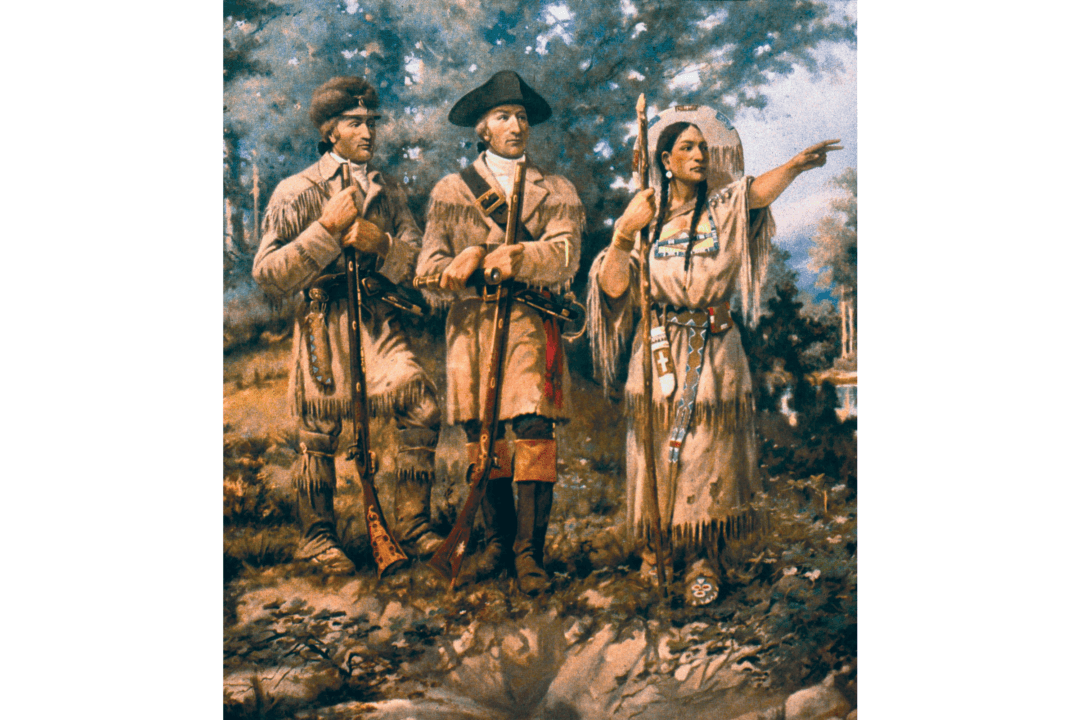

It is an image known to every schoolchild: a Shoshone woman carrying a baby on her back through the wilderness. Sacagawea is probably the most memorialized woman in the history of the United States. Though mentioned only occasionally in journals by various members of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery, and usually not by name, she was crucial to the journey’s success. But she was not always recognized as playing a central role, and though this has changed, the woman behind the legend remains elusive.

Meeting Sacagawea

Statue of Sacagawea and her son, sculpted by Alice Cooper, Washington Park, Portland, Ore. EncMstr/CC BY-SA 3.0