“In the [first] fifteen years [of field work], I can remember just ten times when I had really narrow escapes from death. Two were from drowning in typhoons, one was when our boat was charged by a wounded whale, once my wife and I were nearly eaten by wild dogs, once we were in great danger from fanatical lama priests, two were close calls when I fell over cliffs, once was nearly caught by a huge python, and twice I might have been killed by bandits.”

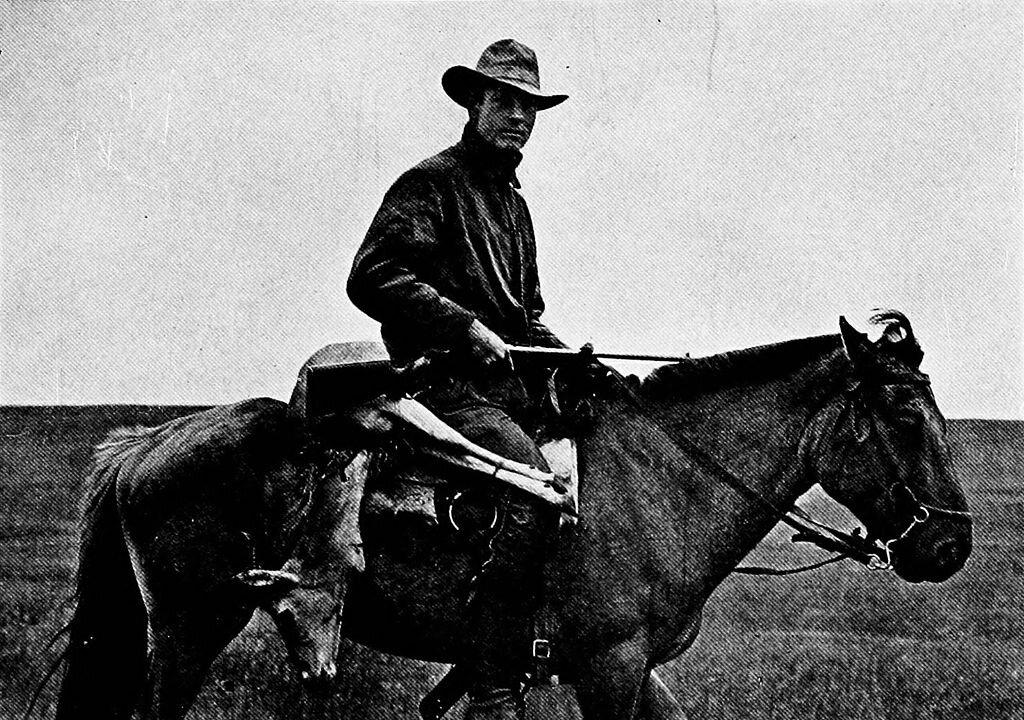

Roy Chapman Andrews (1884–1960) loved adventure, danger, and exploration, as evident from the above quote. Growing up in Beloit, Wisconsin, he went on solo hunts with a single-barrel shotgun that he received when he was 9. Often what he killed, he taxidermized, having studied William Hornaday’s “Taxidermy and Home Decoration.” He soon made a business out of taxidermy, which paid his way to Beloit College, where he earned an English degree in 1906.