The Gilded Age was the penultimate period of the America’s Industrial Revolution. The rise of the railroad, oil, and steel industries supported massive economic and geographic expansion. Electric power gave rise to the light bulb and telephone. And, nearly a generation after the Civil War, power politics between Democrats and Republicans had resurfaced. If the Gilded Age had a face, it would arguably be the face of one of two men: Theodore Roosevelt or Henry Cabot Lodge.

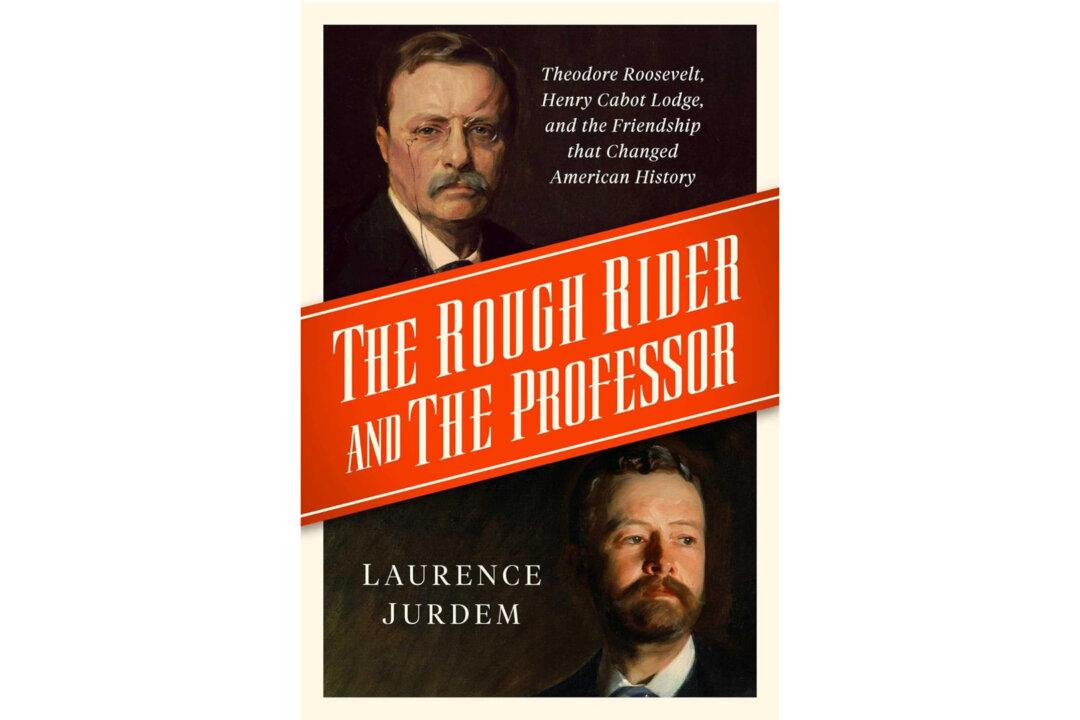

According to Laurence Jurdem, historian and author of “The Rough Rider and the Professor: Theodore Roosevelt, Henry Cabot Lodge, and the Friendship that Changed American History,” Roosevelt and Lodge were cut from the same cloth. The two had very similar upbringings. Both grew up in the privileged surroundings of the northeast: Roosevelt in New York’s Gramercy Park and Lodge in Boston’s Beacon Hill. They both attended Harvard―Lodge seven years prior to Roosevelt. They received a sense of civic duty from their fathers, whom they adored, yet lost at a young age. Roosevelt’s father died during his freshman year of college, and Lodge much younger at 12 years old. Their love of history, literature, sports, and politics were nearly identical. They both traveled extensively. And, their most consequential similarity was that they were both, at least initially, Progressive Republicans.