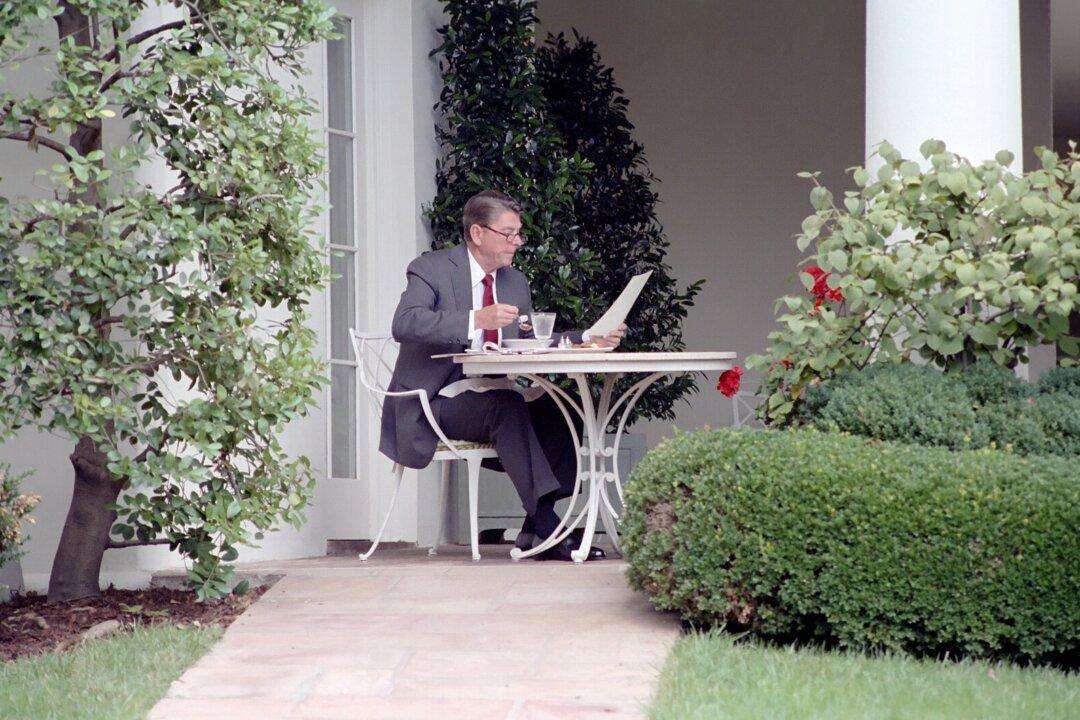

Ronald Reagan’s fans often recollect him as portrayed in the recently released film “Reagan”: a one-time athlete who enjoyed horseback riding and the outdoors, an actor who became first a governor and then a two-term president, and the “Great Communicator” whose policies helped bring about the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Reagan’s critics had a different take on the man. Democrat and presidential adviser Clark Clifford once called Reagan “an amiable dunce.” Political commentator and essayist Christopher Hitchens described him as “dumb as a stump.” Others in the media took Reagan to task as being ill-prepared for the White House, ridiculed him for his Strategic Defense Initiative, which they dubbed “Star Wars,” and were appalled when he described the Soviet Union as an “evil empire.”