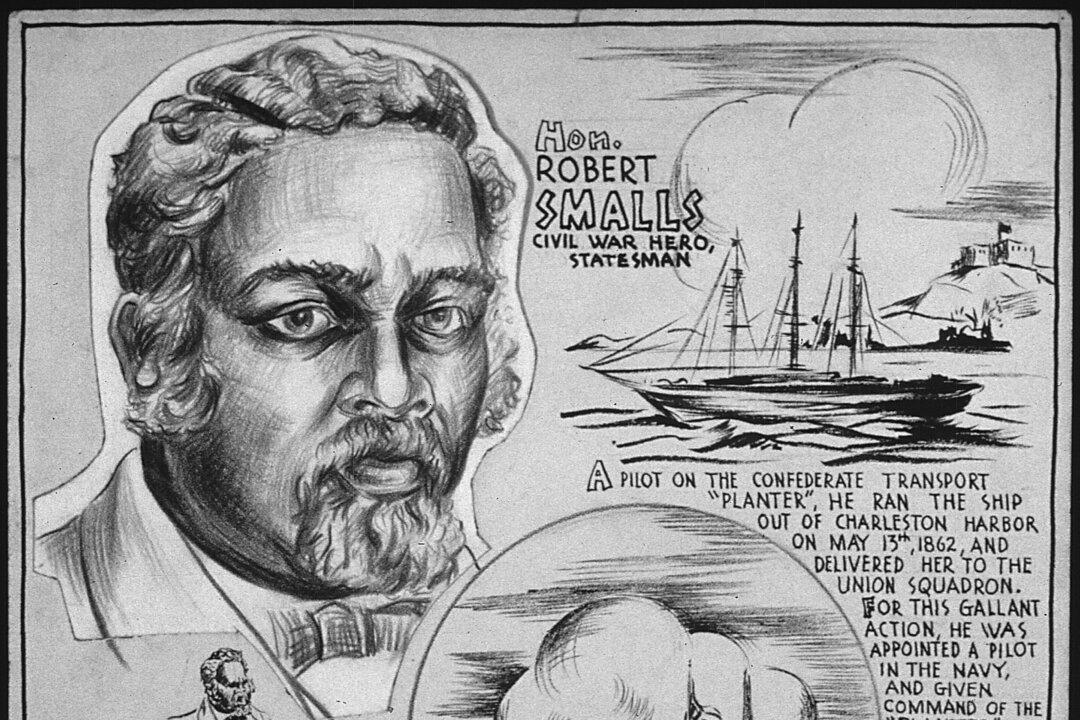

Fearing for his family, Robert Smalls (1839–1915) led a daring, heroic escape from slavery during the Civil War. After the war, he became one of the South’s most influential Republican politicians during the Reconstruction era.

Smalls’s mother Lydia Polite was a slave on the estate of the McKee family in Beaufort, South Carolina, and gave birth to Smalls on April 5, 1839. The young slave grew up in the family household and didn’t work in the plantation fields. When he was 12, his owner sent him to work odd jobs in Charleston, including working at a hotel.