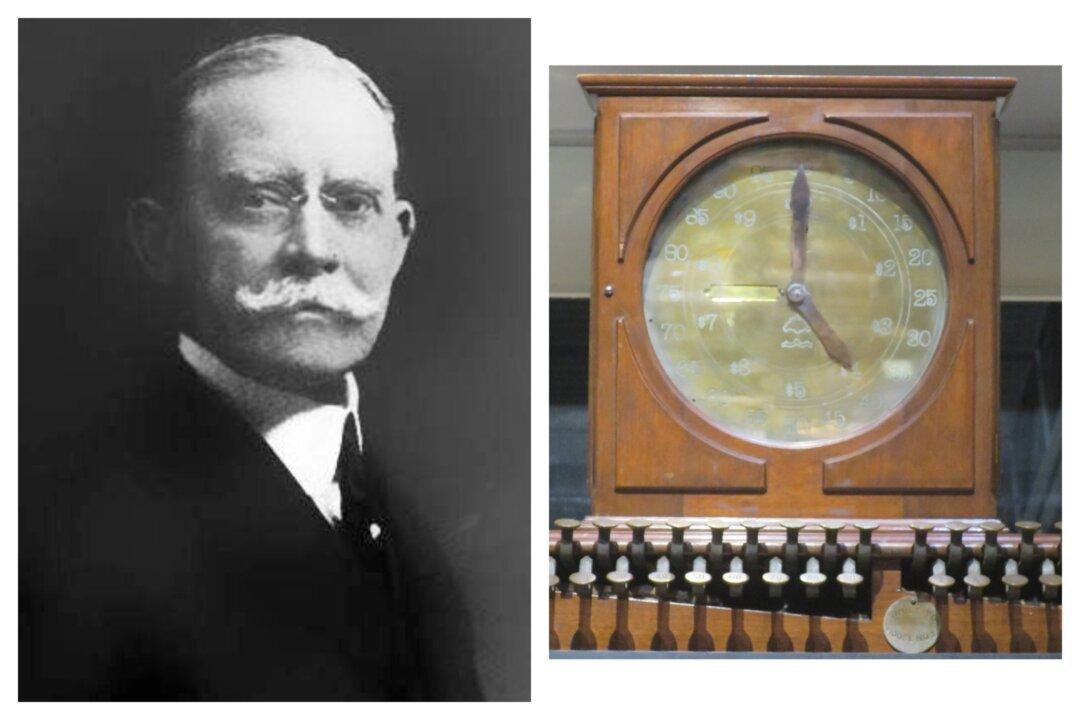

Employees, especially management and sales personnel, were always on thin ice when dealing with John H. Patterson (1844–1922).

He once asked a plant manager if he was satisfied with operations in the plant. “Yes,” the man replied. “We have great workers and make great products; I am totally satisfied.” Believing that only dissatisfaction brought success, Patterson fired him on the spot. On another occasion, an employee began a talk saying, “I’m not very good at public speaking,” to which Patterson countered, “Then why are you speaking? Sit down!” The man was soon fired.