Once upon a time, an understanding of the ancient past was the hallmark of any educated person in the West. A study of classical authors, including Plutarch and Cicero, was a staple of education that has fallen out of vogue. This course of study is by no means an outdated source without value to us in the modern day; rather, it is worthy of revival.

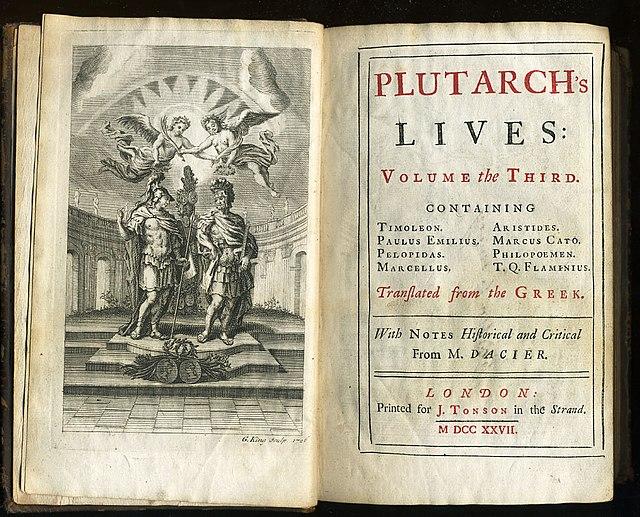

Our Founding Fathers were steeped in the ancients, and Plutarch was primary among them. I was reminded of this recently when I spied several volumes of Plutarch in the library of Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. The works of Plutarch were evidently also included in the Franklin family library: Benjamin Franklin wrote in his autobiography, “My father’s little library consisted chiefly of books in polemic divinity. … However, there was among them Plutarch’s “Lives,” in which I read abundantly, and I still think that time spent to great advantages.”