“Fellow citizens, we cannot escape history.”

One month before Abraham Lincoln took the oath of office, the Texas State Legislature issued the Joint Resolution Relative to Coercion. This short and bold document captured the unapologetic pride that ran rampant among many Southern politicians just before the start of the Civil War. More importantly, it identified one of the most potent fears among white Southerners—a fear so strong that it helped fill the ranks of the Confederate Army for almost four years, “we shall make common cause ... in resisting by all means and to the last extremity such unconstitutional violence and tyrannical usurpation of power.”

Historians will debate the causes and triggers of the Civil War for generations to come, but undeniably, at the root of at least some of the bloodshed lies the question of power. Which body is legally supreme, the Federal or State government? Who has the stronger army and navy? Does one man have the right to own another? Does one region have the right to impose its values over another?

Perhaps the bloodiest laboratory in American history, the Civil War was essentially an experimentation in power. The questions left unanswered by the Founding Fathers were explored on gore-filled battlefields and examined under the bloody lens of trial and error.

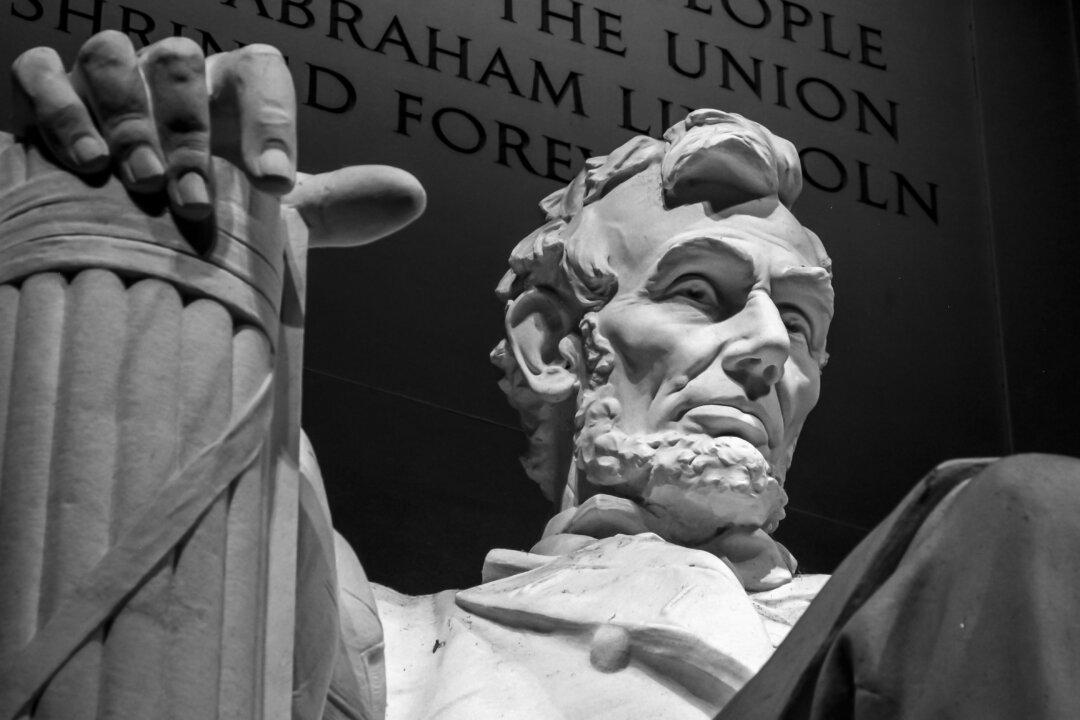

Yet despite the chaos and rending of the governmental fabric, the purpose of power could not have been demonstrated more profoundly than by Abraham Lincoln. At a time when all the precedents that had come before were washed away, President Lincoln forged a unique balance between unyielding determination and flexibility. He admitted when he was wrong, found new ways to adapt to challenges, and most importantly, he never stopped questioning the source of his own power.

Perhaps the greatest testament to Lincoln’s leadership skills is the fact that he defined his role in the conflict to be that of public servant. His actions, positive and negative, could all be traced back his oath of office. Lincoln swore to uphold the Constitution and was willing to do everything necessary—even if it disagreed with his own personal philosophy—to fulfill the vow he took on the day he became president.

There is a tragic irony in reading passionate words of freedom when they were proclaimed by Southern men who sought to own others. But when read in contrast to Lincoln’s own words, they offer a profound lesson: power is merely a tool of man. What is tyranny to one person is the means to achieve freedom to another. True leaders are not those who simply wield power, they are the ones willing to question their own, and determine the purpose behind such might.

The Power to Serve

Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not, I can say, for one, that I have no other so great as that of being truly esteemed of my fellow-men, by rendering myself worthy of their esteem. How far I shall succeed in gratifying this ambition is yet to be developed.

—Open letter to the People of Sangamo County; March 19, 1832

I freely acknowledge myself the servant of the people, according to the bond of service—the United States Constitution; and that, as such, I am responsible to them.

—Letter to James C. Conkling; August 26, 1863

I am filled with deep emotion at finding myself standing here, in this place, where were collected together the wisdom, the patriotism, the devotion to principle, from which sprang the institutions under which we live. You have kindly suggested to me that in my hands is the task of restoring peace to the present distracted condition of the country. I can say in return, Sir, that all the political sentiments I entertain have been drawn, so far as I have been able to draw them, from the sentiments which originated and were given to the world from this hall. I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.

—Speech at Independence Hall; February 22, 1861

I fully appreciate the present peril the country is in, and the weight of responsibility on me.

—Letter to Alexander Stephens; December 22, 1860

If there is anything wanting which is within my power to give, do not fail to let me know it.

—Letter to Gen. Grant; April 30, 1864

If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it.

—Letter to Horace Greeley; August 22, 1862

Most governments have been based, practically, on the denial of equal rights of men, as I have, in part, stated them; ours began, by affirming those rights. They said, some men are too ignorant, and vicious to share in government. Possibly so, said we; and, by your system, you would always keep them ignorant, and vicious. We proposed to give all a chance; and we expected the weak to grow stronger, the ignorant, wiser; and all the better, and happier together. We made the experiment; and the fruit is before us. Look at it—think of it.

—Fragment; written circa July 1854

I recollect thinking then, boy even though I was, that there must have been something more than common that these men struggled for. I am exceedingly anxious that that thing, that something even more than national independence; that something that held out a great promise to all the people of the world for all time to come, I am exceedingly anxious that this Union, the Constitution, and the liberties of the people shall be perpetuated in accordance with the original idea for which the struggle was made, and I shall be most happy indeed if I shall be an humble instrument in the hands of the Almighty, and of this, His most chosen people, for perpetuating the object of that great struggle.

—Speech at Trenton, New Jersey; February 21, 1861

I therefore consider that, in view of the Constitution and the laws, the Union is unbroken; and, to the extent of my ability, I shall take care, as the Constitution itself expressly enjoins upon me, that the laws of the Union be faithfully executed in all the states. Doing this I deem to be only a simple duty on my part; and I shall perform it, so far as practicable, unless my rightful masters, the American people, shall withhold the requisite means, or, in some authoritative manner, direct the contrary. I trust this will not be regarded as a menace, but only as the declared purpose of the Union that it will constitutionally defend, and maintain itself.

—Lincoln’s first Inaugural Address; March 4, 1861

Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history. We of this Congress and this administration, will be remembered in spite of ourselves. No personal significances, or insignificance, can spare one or another of us. The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation. We say we are for the Union. The world knows we do know how to save it.

—Message to Congress; December 1, 1862

(To be continued...)